Latest updates

Exploring identity through poetry: a kōrero with Matariki Bennett

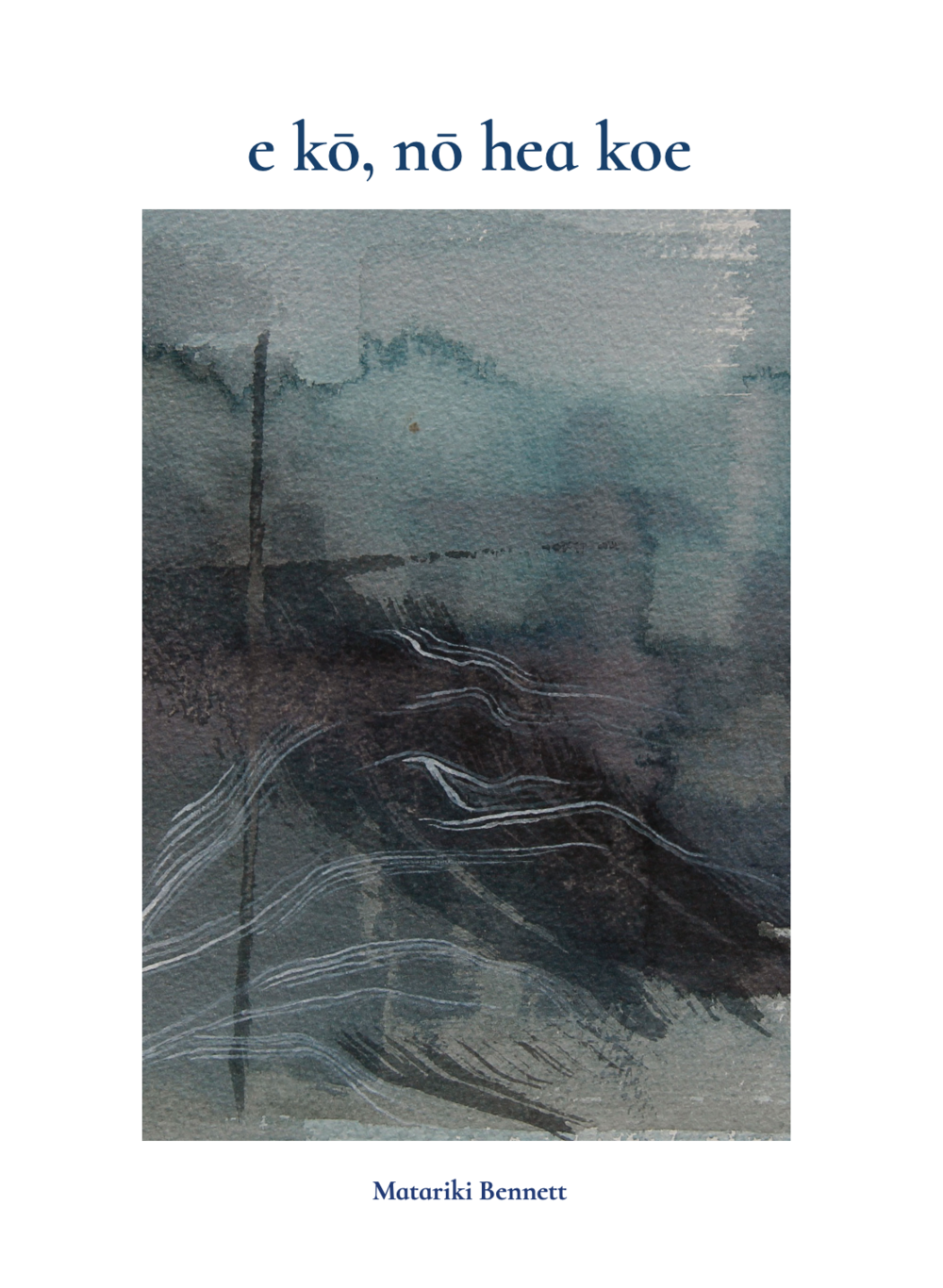

You may have heard of Matariki Bennett (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Hinerangi) as a filmmaker, slam poet, on Re News, or as founder of Ngā Hinepūkōrero. We caught up with her following the release of her debut poetry collection, 'e kō, nō hea koe,' to talk all things creativity.

People might know you from a few creative pursuits, but one of them is as Wellington Slam Poetry Champion in 2023. What drew you to slam poetry - what makes it special?

Poetry has always been around in my whānau - my parents love words and their parents love words. Growing up I gravitated toward short stories, and I always thought one day I would publish a novel.

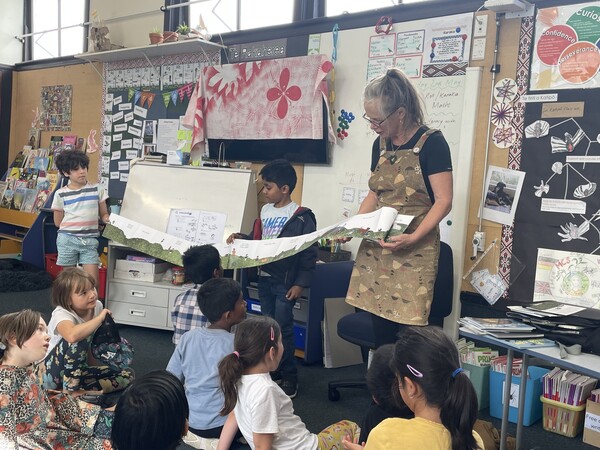

When I was 14 my friend, Manaia Tuwhare-Hoani and I found a video of a spoken word performance when we were in class. Our teacher, Whaea Alice ignored the fact that we were on Facebook when we should’ve been learning, instead she embraced how excited we were by this new genre of writing we had discovered, and she got in contact with Action Education who opened up the world of slam poetry to us.

Poetry really clicked. The performance side of things made it all the more exciting. At kura, in terms of performance, there was Kapa Haka and Manu Kōrero. I wasn’t very good at either of those, so when my friends and I formed the poetry collective, Ngā Hinepūkōrero, I felt like I had finally found my place.

You’re also a filmmaker - can you tell us a little about your films, and how that creative work

informs your writing (or vice versa)?

I have been making films on and off for the past 5 years. My first film, Tōku Reo was made when I was studying at South Seas Film and Television School. It is the story of a daughter learning her language to heal generational mamae of language loss, and inspiring her Pāpā to learn. My second film, a short documentary called Wind, Song and Rain follows fellow poet, Manaia Tuwhare-Hoani as she retraces her Koro, Hone Tuwhare’s steps by returning to his crib at Kaka point and writing a poem to him.

All of my creative mahi informs each other - I find myself leaning into stories of poets when writing for the screen, and I picture scenes playing out when writing poems.

Congratulations on the release of ‘e kō, nō hea koe’. You’ve described your book as ‘born years

ago in my friend’s garage’. Can you tell us more about that?

A lot of my friends are poets, when we were teenagers we would all end up at someone’s house / in someone’s garage after a poetry open mic, buzzing with ideas. This is where many poems began, forming the bones of what became the book.

How did you find the process of producing your first written poetry book?

It was challenging, but I gave myself realistic timelines and goals. When I first began writing the book, I mapped out what the next six months would look like - research phase, brainstorm phase, writing phase, editing phase. Each morning I’d set intentions for the day and I’d write reflections in the evening to hold myself accountable. I never expected too much, which meant that some days not a word was written - what was important was that I was doing something to further develop my ideas!

I spent a lot of time reading and researching historic events that I touch on and deep diving into my whānau history, and then spent loooooots of time brainstorming. This meant that when I finally began to write, I had a whole lot to go back to when I was lacking direction in my writing. I learnt so much throughout this time and I know there is so much still ahead of me. That is something I keep reminding myself - I am only at the beginning.

Your sister’s art in your book sits so beautifully amongst the poems - as you say, they sing to each other! How did you know they needed to be a part of the book?

My whole family works creatively together, something I am forever grateful for. When I began thinking up this pukapuka, I knew I wouldn’t be doing it alone. There was no question that my sister's art would co-exist with my words! My mum’s Motherlines paintings are on the cover of the book and I think my sister and I being within the pages is a continuation of that Motherline whakaaro.

Place keeps coming to the fore in these poems, roaming around Tāmaki Makaurau but further afield too, in Pōneke, Rotorua, and even further to Sydney and Ireland. How did it come to be such a central part?

e kō, nō hea koe is an exploration of identity, so in my brainstorm phase, I asked myself what makes up an individual's identity. What I found (broadly speaking) was that people, places, memory and whakapapa inform the way we identify ourselves and mark our place in the world.

Naturally, places were the start point for me - being able to look at a place and sift through memories of that place to then begin finding the significance of it to me. Tāmaki Makaurau is where most of the book lingers, as this is where I spent my youth. Pōneke is now home, so later in the book there are poems situated here. Rotorua and Ireland are where my whānau whakapapa back to and Sydney is where my parents met.

Why do you think it was poetry that allowed you to carry out this exploration of whakapapa?

I was so lucky to write full time for six months. I am most drawn to writing about my whānau and whakapapa, so I used this time to research, meeting my whānaunga through recordings on the Sound Archives and going back home to Rotorua and Ireland.

All of this exploration enriches my poetry, as it is not something done alone. It is the amalgamation of generations of love, of words and of stories.

There’s a beautiful flow between English and reo Māori, how did you navigate this balance?

My parents made sure my siblings and I grew up with our Reo Rangatira, we all went through Kōhanga and Kura, so I have always been bilingual. I write how I speak day to day, flowing between both languages.

There are so many things that you can say in Te Reo Māori that cannot be translated and that is why I have two full Reo Māori poems in the book with no translation. I think it’s a wero to those reading, kia whakapakari ai te reo.