Latest updates

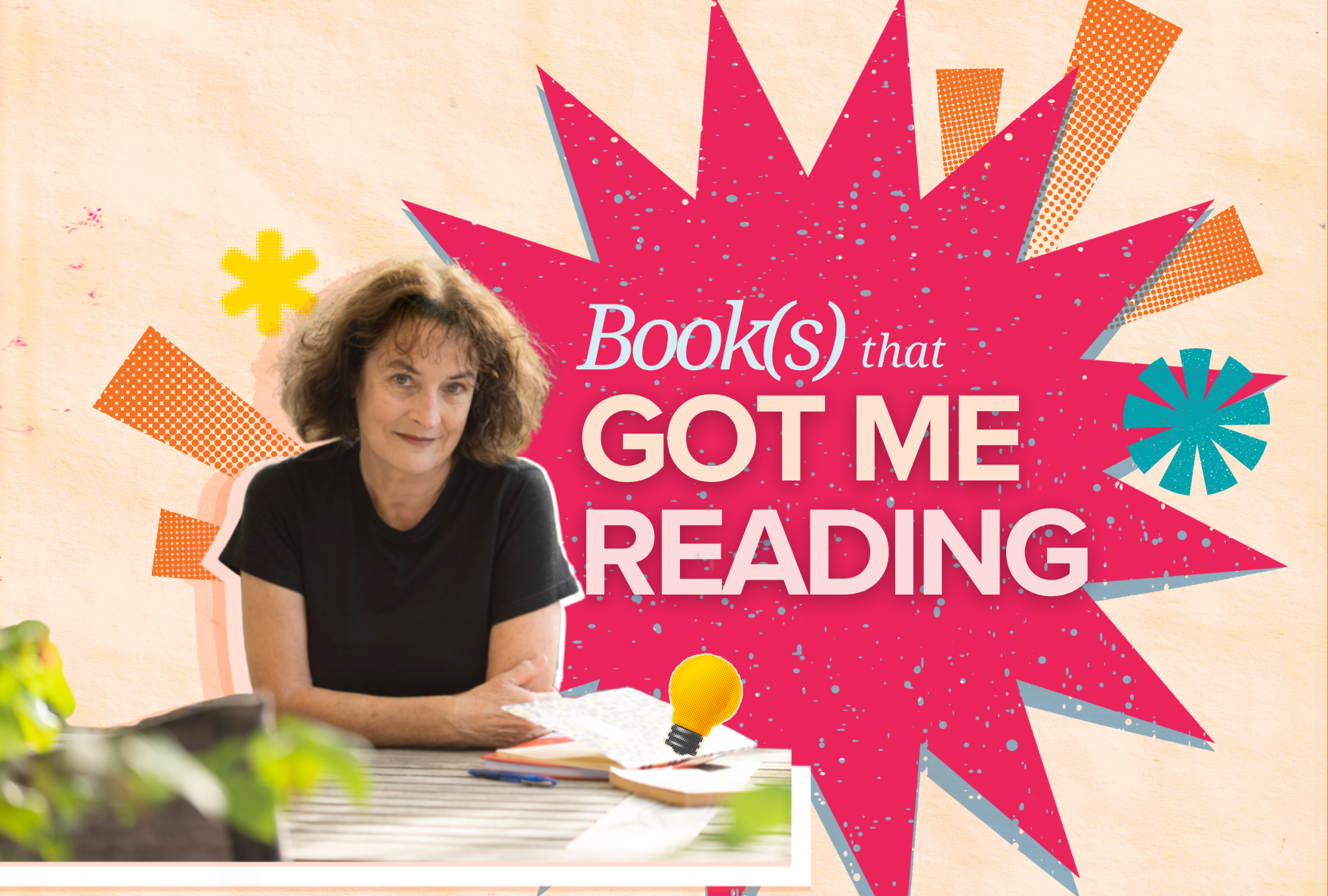

Kate De Goldi: The Book(s) That Made Me a Reader

A new series where we ask reading champions in Aotearoa New Zealand what book got them hooked on books. None of them are willing to narrow it down to just one, but that's half of the fun.

Kate De Goldi, Te Awhi Rito

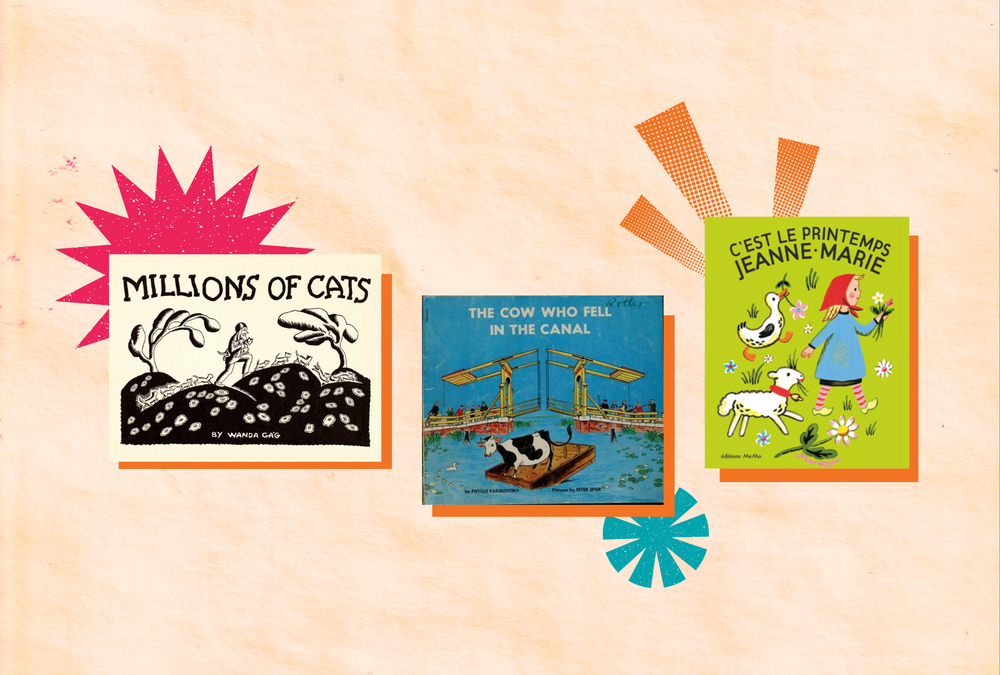

Of course, there was no one book that made me a reader. There were countless books that pinned me to the page and whetted the appetite for more and more. In the beginning was a succession of picture books; three titles loom large because of the circumstances in which they were read to me.

Next door, when I was a child, lived Dr Margarete Mayer, a lecturer in botany at Canterbury University. Dr Mayer (we always called her this) was Jewish and had fled Germany with her parents in the 1930s, pitching up eventually in New Zealand. The Mayer house was, to my young eye, straight from a fairytale – a wild garden, overgrown trees that hugged the house and, inside, furniture, fabrics, food, books, the very smells, both unfamiliar and enchanting.

My friend Lily and I went sometimes for afternoon tea – an unvarying ritual with buttered toast, boiled eggs and spice biscuits. After tea, we trailed Dr Mayer down the dark hallway – peering into bedrooms and her father’s office where his wire-framed glasses lay neatly folded on the desk – to the front room, with vast book cases and crumpled sofas. Lily and I sat tucked into either side of Dr Mayer while she read, in her gutteral, expressive English: Millions of Cats, The Cow that Fell into the Canal, and Springtime for Jeanne-Marie. This experience remains the most memorable of my early life with books, and those three are inflected still with the magical otherness of Dr Mayer’s world.

My parents certainly read to us at bedtime but, curiously, I have no memory of these books, except one about a day at the beach, and only because our dad, apropos of nothing in particular, regularly busted out the final line of the story: We’ll be back! You bet we will! I have often thought this line sums up my life-long relationship with books: a tremendous time had, and a determination to get back there as soon as possible …

We went to the library regularly with our dad, but our mother bought us books – Puffin books, with the mysterious words on the publishing page, Editor: Kaye Webb. I had no idea what an editor was, much less a Kaye Webb, but these words became an imprimatur for me, the assurance of transport to another place. Decades later, reading Francis Spufford’s memoir, The Child that Books Built, his description of Puffin paperbacks and that imprint’s domination of post-War children’s publishing summoned precisely my inarticulable childhood satisfaction at the sight of the plump puffin on those book spines: ‘It was as if Puffin were part of the administration of the world. They were the department of the welfare state responsible for the distribution of narrative.’

My mother’s good friend Jenny Zwartz, an enthusiastic reader of children’s literature, guided Mum’s book buying. Like many children in the ‘thirties and ‘forties, our mother was familiar with the children’s classics that jumped generations – Heidi, Anne of Green Gables, Seven Little Australians, etc; but Jenny, who’d spent several years in London in the early 1950s when the second golden age of children’s publishing was hitting its stride, had read widely and deeply in the form.

It was Jenny who gave me the first book in what became my own library – that is, the collection of books in my bedroom I hoarded as my own. In each book I grandly wrote my full name, then fell into the story; afterwards, I filed the book with great satisfaction, according to whichever of my peculiar categorising principles was currently in play. I read and reread these books continously throughout my childhood, and many of them I still revisit. Without doubt, they built and formed my reading and writing self.

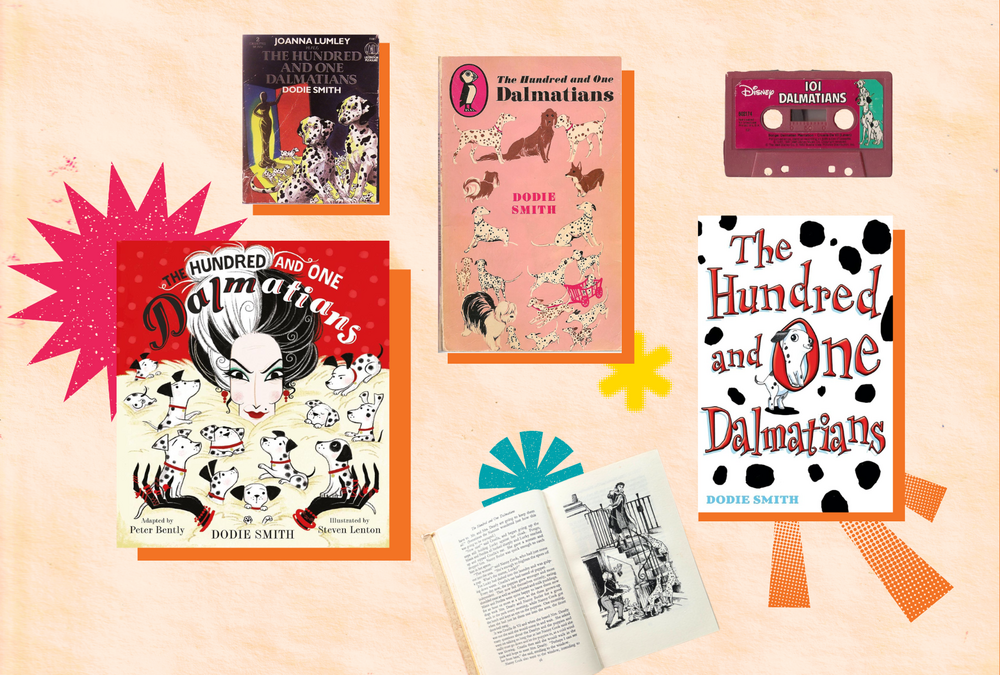

That foundational Puffin from Jenny was The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith. Though I can’t say this book alone made me a reader, nevertheless it was totemic in my reading life – my first proper novel, but also one that came from someone I liked enormously, who knew children’s books intimately, who collected them and revelled in them. In short, a reading model.

I read that book so many times it eventually fell apart. I bought another at some stage, but I still have the tattered original in the cardboard box where loved and decrepit paperbacks go to live out their twilight years.

The Hundred and One Dalmatians is an enduring classic for good reason. Pongo and Missis’s adventure to recover their stolen puppies is masterfully plotted, full of amusing, fallible characters, and it carries the reader through a storm of emotions. It’s a story of family lost and regained, a journey story, with dangers aplenty, narrow escapes, chance discoveries, and the comforts of cameraderie. It also has one of the great villains in children’s fiction, Cruella de Vil, upon whom a thoroughly satisfactory revenge is finally visited.

It’s also a children’s book that has always been read and enjoyed by adults; Smith employs a double address – immersive plot and interesting relationships for a young reader, but plenty of word play, winks, and jokes for an adult. I remember my glee each time I returned to the book and a previously puzzling comment became suddenly explicable and properly funny. For instance, while the Baddun brothers (obviously bounders) are glued to their favourite tv programme ‘What’s my Crime?’ and the 97 pups are being prepared in hushed tones for escape, Smith inserts one of her occasional asides: ‘Stern moralists said this programme was causing a crime wave and filling the prisons, because people committed crimes in the hope of being contestants. But crime is usually waving … I thought this hilarious when I finally twigged to it. In my recent reading, preparing for this piece, I was astonished by a never-before-clocked witticism: Pongo and his dashing pup Lucky are scouring Hell Hall for any remaining food to sustain the puppies on the long trek back to London.

‘Anything in that cupboard?’ said Pongo, at last.

‘Only coke for the central-heating furnace,’ said Lucky. ‘Well, the Badduns won’t find anything to eat tomorrow, will they?’

‘Let them eat coke,’ said Pongo [!!!]

Dalmatians was written on Smith’s return to England after the War years spent in America. The book is so clearly a love-song to everything English. Eccentricity, bucolia, dog-love, stoicism, the Englishman in his ‘castle’ (or the green and pleasant environs of Regent’s Park, London, where the upper class Dearlys live with Nanny Butler and Nanny Cook).

One of the most amusing aspects of the book is the anthropomorphising of the various dogs who help Pongo and Missus on their perilous way to and from Suffolk – all English stereotypes. The burly Golden Retriever is an enterprising innkeeper, with a nose for sales opportunities; the black spaniel in his manor house, a courtly, faded aristocrat; funniest of all is the Sheepdog – Colonel – who has located and watched over the imprisoned pups. He has a military bearing, is formidably organised, and always ready to give a promotion up the army ranks. His sidekick Puss Tibs quickly becomes a Lieutenant. Lucky, eager and brave, climbs rapidly from Sergeant to Sar’-Major to Captain. After successfully supervising the pups’ escape the Colonel bestows on himself the rank of Brigadier-General.

Like many English children’s books written in this period, the recent War hovers. Food is abundant in the novel – sundry steaks and baked goods for the travelling pups – in defiance of the rationing imposed in the real world. The ‘spirit of the Blitz’ is in play – the dog community across south England pulls together, despite the dangers, to help the afflicted. There are even faint echoes of Churchillian rhetoric. Once the Brigadier-General has seen the Dalmatian ‘army’ safely off back to London, he goes after the Badduns, who are searching the fields for the puppies: ‘… he hurled himself at the Badduns and bit both brothers in both legs. Seldom can four legs have been bitten so fast by one dog …’ Ho ho ho.

Of course a contemporary reader notes the sexism and classism (Missis is a loving mother but quite the dingbat, whereas Pongo has every opportunity to prove he owns the Keenest Brain in Dogdom). The Dearlys exist in blithe privilege, pulling the Splendid Vet from his bed at all hours of the night, and ordering steaks for the returned dogs ‘from the Ritz, Savoy, Claridges and other rather good hotels.’ But Smith is a writer from another time and the narrative exists in the hyper-realism of Storyland. All in all, Dalmatians has travelled well down the decades. It remains both an excellent read aloud – a treat for adult and child – and an engrossing solo read.

I was charmed all over again by a favourite episode. On the road home, Cruella de Vil at their heels, the dogs are forced to take refuge in a country church. It’s Christmas Eve and at the front of the church is a large nativity scene. Cadpig, the youngest pup, who has been entranced by the Badduns’ television, is immediately captured by the human and animal statues gathered around the crib.

‘Look, look! Television!’

But it was not like the television at Hell Hall. And the figures on the screen did not move or speak. Indeed it was not a screen. The figures were really there …

A delightful black and white illustration accompanies this scene – a back view of the sooty Cadpig sitting upright on a hassock, spellbound by the nativity, the ‘kind of cow … and kind of horse … ‘No dogs,’ said the Cadpig. ‘What a pity! But I like it much better than ordinary television.’

I did wonder, this time round, if Dodie Smith were making a point about this new bewitching screen entertainment and its contrast with the tranquility and quiet offered by, say, an artwork – or a book. Maybe.

In the closing chapter, Cruella vanquished and England Safe for Dalmatians, the Dearlys have moved to Suffolk, purchased and transformed Hell Hall to house the 101 dogs, and installed a television for the Nannies. Smith leaves the reader with the Cadpig – with a child’s eye on matters and a hopeful sense of the world. Cadpig continues her love affair with the screen:

But during the many happy hours the Cadpig was to sit watching it in the warm kitchen, she never liked it quite so much as that other television – that still, silent television she had seen on Christmas Even … in that strange, lofty building. She often remembered that building, and wondered who owned it – someone very kind, she was sure. For in front of every one of the many seats had been a little carpet-eared, puppy-sized dog-bed.

About Kate

Kate De Goldi is the current Te Awhi Rito New Zealand Reading Ambassador, who advocates for and champions the importance of reading in the lives of young New Zealanders. She is a writer, a dedicated reader and a long-time advocate for the importance of reading at every stage of life.

Kate reviews books in print and broadcast media, and teaches creative writing at schools throughout New Zealand. With Susan Paris, she is co-publisher of the Annual Ink children’s imprint.