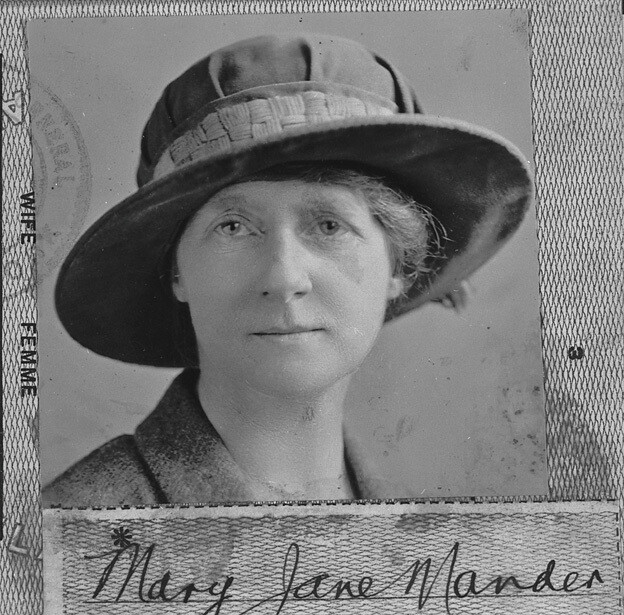

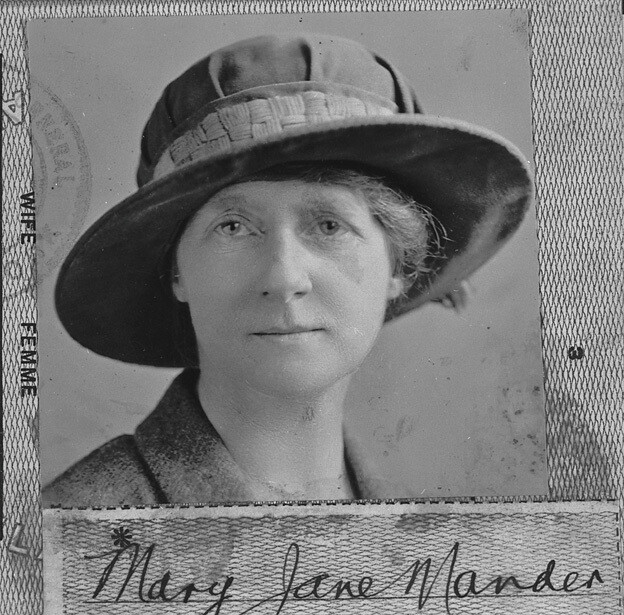

Jane Mander

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

MANDER, Jane (1877–1949), novelist, was born in Ramarama, a small settler community near Auckland. Her father forwent the limited opportunities of settler farming soon after his marriage in 1876, choosing the life of a pioneer lumberman and sawmiller in the great kauri forests north of Auckland. In 1881 he bought a bush mill at Awhitu, the first of many endeavours which caused the family to move (Mander estimated) twenty-nine times during her upbringing, often living in hardship. One such home was Pukekaroro, a tiny settlement near Kaiwaka on the Otamatea river which subsequently provided the details of the setting for her first novel, The Story of a New Zealand River.

The conditions of Mander’s nomadic childhood find expression in her fiction: settler characters and concerns remain largely peripheral to her four novels set in New Zealand, all of which deal with pioneering life. Unlike her mother, who succumbed to invalidism in the face of years of isolation and discomfort, Mander viewed change as opportunity; this is evident in the note of change, weighted with expectation and promise, on which many of her novels end. Her sporadic education at schools often great distances away was supplemented by her mother’s tuition, and she reached standard six in 1892. As there was no high school nearby (the family was now living in Port Alfred), she became a teacher-pupil at the local primary school, teaching in a variety of schools in the ensuing years. She matriculated through extramural study in 1897. When the family moved to Whangarei in 1900 Mander gave up teaching, temporarily capitulating to expectations that she conform to the model of passive Victorian daughter. Two years later her father Frank ran for parliament on the side of Massey’s Reform Party and, aided in his campaign by his eldest daughter, narrowly ousted the sitting member for Marsden. He spent twenty years as a member of parliament and a further seven as a member of the legislative council. That same year his purchase of the main newspaper of the north, the Northern Advocate, provided Mander with the opportunity to try her hand at journalism; she worked as sub-editor and reporter, and eventually ran the editorial department single-handed.

After a brief trip to Sydney in 1907, Mander took over the editorship of the Dargaville North Auckland Times. She returned to Sydney in 1910 and was befriended by W.A. Holman, who became the Labour Party premier of New South Wales. Here Mander occupied herself writing freelance journalism (she submitted articles to the Maoriland Worker under the pseudonym of ‘Manda Lloyd’) and studying languages. Determined to win her father’s favour (and financial support) to study journalism at Columbia University in New York, she again returned to New Zealand in 1912. In June that year, aged 35, she sailed for New York, travelling via London, carrying with her the script of a novel which she offered to four publishers, all of whom declined it.

At Columbia Mander excelled, achieving the highest grades in examinations at the end of her first and second years, a remarkable feat given that she also held numerous part-time jobs—lecturing, coaching younger students, writing for magazines—to supplement her meagre income. During this time she continued to rework her novel but, after another rejection, finally abandoned it. While she may have inherited tenacity, courage and energy from her father, Mander did not inherit his good health. Financial pressure and overwork exacerbated her poor health, and she was forced to abandon her studies in her third year. Known for her liberal feminism, she joined the suffrage movement in 1915 and campaigned for the New York State referendum on women’s franchise. In the course of the next two years she ran a hostel for girls, pursued research at Sing Sing prison and worked for various war effort organisations, taking an administrative post in the Red Cross when the United States entered World War 1. During this time she worked on a new novel, which was accepted by John Lane in 1917 and published in 1920: The Story of a New Zealand River.

Despite being well received in England and the USA, The Story of a New Zealand River was poorly reviewed in New Zealand. Lacking precedents for a local literature, critics reproved the novel’s failure to conform to the familiar conventions of the nineteenth-century regional British novel in theme and content. Reviewers expected documentary literalism in a novel so liberally sprinkled with real place names and details of actual events; many were critical of the creative fiat with which the novelist altered geography and population to suit her artistic vision. Furthermore, colonial readers found the novel too outspoken on matters of sex and religion. The New Zealand Herald, in 1920, proclaimed The River’s liberal ending ‘too early for good public morality’; it was set aside in the ‘Reserve’ section of libraries to be borrowed by approved adults only on special request to the librarian.

Mander’s next three novels were all set in New Zealand, drawing directly on her childhood experiences of pioneering life in the north. The Passionate Puritan (1921) is a rather cheerful account of kauri milling, apparently written with an eye on the cinema (‘a mistake’, Mander claimed, she ‘ever afterwards regretted’). Two long documentary sections—the tripping of the dam and the bush fire—are woven into the light-hearted romance theme, which centres around the liberation of the central character, Sidney Carey, from the shackles of puritanism. The Strange Attraction (1922), the weakest of Mander’s New Zealand novels, focuses on the concerns of a thriving second-generation community in Dargaville on the Wairoa river: the rivalry of two newspapers and a contested parliamentary election. Her political concerns and vivid portrayal of an emergent community sit uncomfortably alongside the somewhat indulgent melodramatic romance plot detailing Valerie Carr’s love for Dane Barrington, and her release from their disintegrating secret marriage when Dane heroically departs on learning he has terminal cancer. Despite their moderate success abroad, the New Zealand response to these novels was again almost wholly negative. Critical attention focused on Mander’s purported failure to portray convincingly ‘representative’ members of the communities she chose to sketch, on her putative moral deviance, and her continued obsession with what was labelled ‘the sex problem’. Mander responded from London to her critics in a letter to the Auckland Star in 1924: ‘a writer who is trying to be an artist, as I sincerely am, has nothing whatsoever to do with being a tourist agent, or a photographer, or a historian, or a compiler of community statistics. I am simply trying to be honest and loyal to my own experience’; and ‘as a matter of fact I’m not half sexy enough for thousands of readers here’.

In 1923 Mander had left New York for London, where she worked as a publisher’s reader and then as the English editor for the Harrison Press of Paris. During this time she wrote some sketches, short stories and essays and acted as the London correspondent for various New Zealand newspapers. As almost all of Mander’s private correspondence has been destroyed, one cannot be sure of the novelist’s response to negative reviews of her books as they trickled in from her own country. It is worth noting, however, that Allen Adair (1925) was her last novel with a New Zealand setting, as if she wilfully turned her back on the unreceptive readers of her home country and directed her writing towards those more willing to appreciate its strengths and tolerate its weaknesses: The Besieging City (1926) is set in New York; and Pins and Pinnacles (1928) is set in London and Paris.

Mander completed another novel in 1931, but destroyed it after its rejection by one publisher. The death of her mother imminent, and her own health failing, she returned to New Zealand in 1932. Having championed the advances of New Zealand abroad for two decades, Mander was now bitterly disappointed in her country, which to her mind had failed to fulfil its potential and had become ‘one of the backward people of the earth’. The puritanical malaise, so often attacked in her New Zealand novels, was a condition she now found rampant, threatening to dissipate the energies and promise of the pioneers. It is deeply ironical that it is precisely this puritanical, imitative colonialism which marked the response of her original New Zealand readers to her novels. Illness, years of pedestrian literary work, and an intolerant local audience combined to wither her creativity. Her energy drained in the care of her father, Mander’s attempts at writing her commissioned seventh novel and reminiscences all ended in illness, and she wrote nothing more than a few articles, reviews and radio scripts until her death in Whangarei, at the age of 72.

By no means New Zealand’s most accomplished novelist, Mander remains one of its most important, for in a relatively early period she was willing to make a creative commitment to life in New Zealand. She writes with an intimate sense of belonging to this country and a fervent love of it; her work is undistorted by either exaggerated enthusiasm or the colonial cultural cringe. In this she resembles Olive Schreiner, whose novel The Story of an African Farm greatly influenced Mander’s first novel (as the title suggests); she hoped to write of New Zealand as Schreiner had done of Southern Africa, evoking a genuine and vivid sense of local flavour. Technically, Mander’s novels evidence ample flaws for the critical reader. Her conventional style is mannered and derivative, strongly influenced by nineteenth-century English novels, although her fine management of terse and controlled dialogue stands in contrast to the overblown wordiness of her descriptive prose: spoken language in the novels is rich in variety and aural nuance and provides a good index to character. But Mander’s greatest strength is in the rendering of the internal conflicts, feelings and attitudes of her characters so that despite their stylistic clumsiness, the novels have enduring emotional intensity and appeal.

Typescripts of the last four novels are held in the Auckland Public Library, along with Mander’s own collection of her journalistic and other prose writing. Copies of this material are held by the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington. The standard critical biography is Dorothea Turner’s Jane Mander (1972). KW.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2007, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'Women Prose Writers to World War I'

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File.