John A. Lee

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Lee, John A. (1891–1982), was born in Dunedin to Scots Romany parents. His father Gipsy Alfredo Lee deserted the family before Lee knew him, becoming a vagrant acrobat and entertainer. The extreme poverty of the family’s life is the context of Lee’s novel Children of the Poor (1934) and of his mother Mary Lee’s proud autobiography The Not So Poor (1992). Poverty breeding crime, Lee became an habitual thief and was sentenced to Burnham Industrial School in April 1906, effectively being made a ward of the state until 21. He broke away time and again, labouring and living on the swag until finally gaoled in Mt Eden. He was freed at last in March 1913. Although no criminal in any real sense, he had lived at odds with the law for seven years.

In World War 1 he lost his left forearm and was awarded the DCM for gallantry at Messines Ridge. On the day he landed back in New Zealand he joined the Labour Party. He became MP for Auckland East 1922–28, and for Grey Lynn 1931–43. From 1936 to 1939 he was Under-Secretary to the Minister of Finance and responsible for the introduction of state housing. The 1930s also saw him achieve fame as a novelist and writer on socialism. In 1940 he was expelled from the Labour Party for attacking the Prime Minister Michael Savage in the pamphlet ‘The Psychopathology of Politics’. Ill with cancer, Savage died just three days later. Lee’s political career was destroyed. He founded the Democratic Labour Party but was never re-elected. He continued to disseminate left-wing socialist views, however, through John A. Lee’s Weekly (1940–48) and other journals well into the 1950s. From 1950 he was a successful Auckland bookseller and writer, adding to his fiction of the 1930s and publishing a number of political memoirs and analyses. As his formal education had stopped at Standard Four he was an exemplary self-educated, self-made man. And although he miscalculated politically in 1940, he never lost the legendary status he had achieved by that time, a status owed in large part to his writings and gift of oratory.

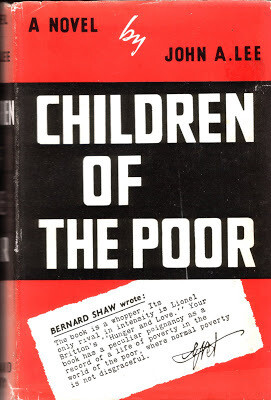

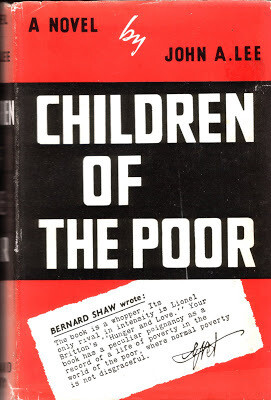

With the exception of the Shiner stories, most of Lee’s best-known works of fiction are autobiographical in origin. Although not published until 1976, his first novel, Soldier, was written in 1918 in England as he recovered from his arm injury in a German grenade attack, and is about that and other personal war experiences. In a later war novel, Civilian into Soldier (1937), Lee writes of the war of ‘John Guy’: Guy was his wife’s maiden name. These are melodramatic novels, stylistically heavy-handed in their attempts to mime war’s assault on the senses, and bold in their sexuality. Written between them, Lee’s first published novel Children of the Poor (1934) and its sequel The Hunted (1936) are very much finer. Dealing with Lee’s life to his imprisonment at the age of 14 and his vain attempts subsequently to escape from Borstal, they are his richest treatment of a theme that pervades his work, man’s inhumanity to man. Both books are marred, the former especially so, by Lee’s inability to achieve aesthetic distance, his constant intrusions in the manner of tracts on economics, criminology, the legal system, sociology, and so on. The wonder is that they survive as ‘novels’ at all, and there is of course a measure of cultural collusion in this. Lee has real talents for creating characters, dialogue, action, incident and place, and writes with such energy and pace that negative critical judgments come to seem inappropriate. The reader is held by a quality of the writer’s personality. The first edition of Children of the Poor was published anonymously. When George Bernard Shaw read it on his way back to Britain in April 1934 he wrote to Lee, ‘Do not remain anonymous longer than you can help. It takes a long time for a name to become known in the world of literature; and you cannot afford to lose a minute of it.’ In the non-autobiographical, amusing anecdotes and yarns of Shining with the Shiner (1944), written almost flauntingly in the year he entered the political wilderness, and in the related volume Shiner Slattery (1964), Lee turns the Otago regional folk hero Ned Slattery (1840–1927) into a national icon, the spirit of beating the Protestant work ethic and surviving by one’s wits. Completely inferior fictions are the potboilers he wrote originally as serials to boost the circulation of his Weekly, The Yanks are Coming (1943) and Mussolini’s Millions (1970). A posthumous novel The Politician (1987) was written fifty years earlier as The Politician and the Fairy.

Lee’s chief political books include Socialism in New Zealand (1938), to which the British Labour Party leader Clement Attlee wrote an introduction, and more importantly his political autobiography Simple on a Soap-Box (1963). Commentators who have difficulty reconciling Lee’s socialism with his exaltation of individual freedom can find assurances in this latter book, such as that ‘Socialism without democracy is merely mechanical regulation of life.’ Rhetoric at the Red Dawn (1965), Political Notebooks (1973) and The John A. Lee Diaries 1936–1940 (1981) shed light on the fortunes of the Labour Party since World War 1. For Mine is the Kingdom (1975) is a scurrilously borderline biography of the ‘Booze Baron’ Sir Ernest Davis. Next to Simple on a Soap-Box the most important of all these works of non-fiction is the openly autobiographical Delinquent Days (1967), which carries on where the novel The Hunted leaves off and ends with Lee’s release from Mt Eden gaol in 1913. More effectively in this book than any other Lee describes the foundations of his humanistic political socialism while on the run from Borstal, in the companionship of labourers and swaggers, and in the left-wing writings of Jack London and Upton Sinclair that he came upon in labourers’ huts. It was that philosophy that sustained him to the end, and informed everything he wrote, that and his ability to respond lyrically to the natural world, seen nowhere more movingly than in Delinquent Days. There are excellent studies of John A. Lee by Erik Olssen and Dennis McEldowney. KA

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File.