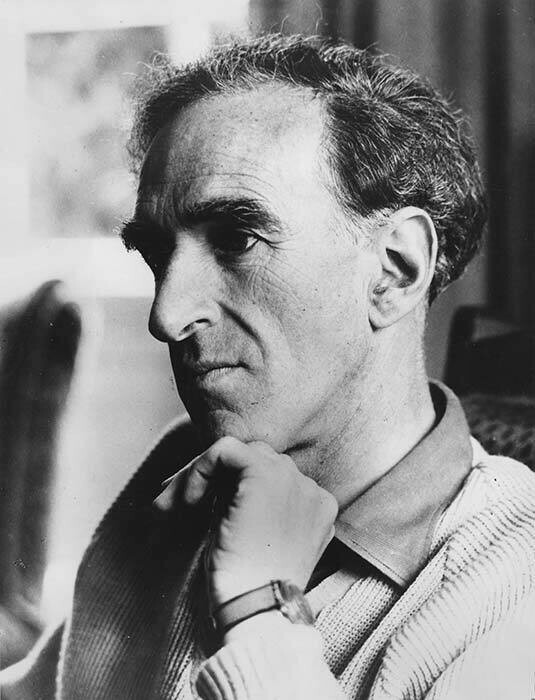

Charles Brasch

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Brasch, Charles (1909–73), was a gifted poet, the distinguished founding editor of Landfall, and a generous and far-sighted patron of the arts. He was born in Dunedin, the only son of parents of Jewish descent. His father was a lawyer, and his mother, who died before Charles was five, was connected to the Hallenstein business dynasty (initially established on the Central Otago goldfields).

Brasch was a boarder at Waitaki BHS 1922–27, when the rector was the well-known Frank Milner. He established lifelong friendships with Ian Milner, son of the rector, and James Bertram, and published his first poems in the school magazine. At 17 he was sent by his father to St John’s College, Oxford.

He did not distinguish himself academically at Oxford (1927–31) but published some poems in university magazines and travelled extensively on the continent. He returned to New Zealand in 1931, and was expected by his father to enter the family business. He became involved with the group—some of them ex-Waitaki friends—who were planning Phoenix, to be published at Auckland University College. Brasch contributed to three of the four issues 1932–33, including some translations from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet.

Temperamentally unsuited to the commercial world, he was determined, despite family disapproval, to become a poet. After what has been described by Bertram as a ‘bitter showdown’ with his father, he went back to England where he remained until the end of World War 2 in 1945, apart from brief visits to New Zealand.

Brasch was based for most of this time in London. Between 1933 and 1935 he spent three seasons on field sites in Egypt as a cadet archaeologist. He also visited Russia with friends in 1934. In 1936 his sister, Lesley, became ill and Brasch accompanied her to Little Missenden in the Chilterns, also teaching there at an experimental school.

In 1938 he went to New Zealand for several months, meeting many of those involved in the literary and artistic movement centred on the Caxton Press in Christchurch, including Denis Glover, Leo Bensemann, Ursula Bethell, Douglas Lilburn, M.T. Woollaston and Rodney Kennedy. He contribued to Tomorrow—the Christchurch-based journal—and in 1939 had his first collection of poems, The Land and the People, published by Caxton. Among some slight and immature work, the title sequence stood out as a portent of things to come.

On his way back to Europe, Brasch crossed America with Milner and Bertram. In England his sister died after a long illness, and while he was travelling to New Zealand with his father after her funeral in 1939, war broke out and he decided to go back to England. Rejected for active war service, he became a fire-watcher during the London blitz and later worked as a civil servant doing intelligence work for the Foreign Office.

Stimulated by the war, Brasch began writing newly mature poems which looked back to his country of origin: ‘It was New Zealand I discovered, not England, because New Zealand lived in me as no other country could live, part of myself as I was part of it, the world I breathed and wore from birth, my seeing and my language’ (Indirections).

These poems include phrases still familiar for their encapsulation of New Zealand experience: ‘Always, in these islands, meeting and parting / Shake us …’; ‘distance looks our way’ (‘The Islands’). They were printed in John Lehmann’s New Writing, along with work by other New Zealanders, including Frank Sargeson and Allen Curnow.

During the war, Brasch was visited in London by Glover, of the Caxton Press, on leave from the Royal Navy. The two writers made plans for a new literary magazine in New Zealand after the war. In these discussions Landfall was conceived, which Brasch was to edit for its first twenty years (1947–66). He returned to New Zealand in late 1945, this time permanently.

Being of independent means, Brasch was able to devote himself to editing Landfall virtually full-time and with the utmost diligence and seriousness. The journal’s character owed much to his predilections. It was at his insistence that, as well as publishing poetry, stories and reviews, Landfall addressed itself to all the arts and to other aspects of public affairs. He included in each issue commentaries on topical activities in theatre, music, the visual arts, architecture and other cultural fields.

He deliberately placed imaginative literature within a social and political context by including lengthy exploratory essays such as T.H. Scott’s ‘From Emigrant to Native’, Bill Pearson’s ‘Fretful Sleepers’ and Robert Chapman’s ‘Fiction and the Social Pattern’. Also noteworthy was the series of essays entitled ‘New Zealand Since the War’. Brasch did much to establish a perspective that was (in his phrase) ‘distinctly of New Zealand without being parochial’.

He encouraged what might be called an enlightened provincialism, recognising that New Zealand was provincial in relation to Europe but nonetheless a centre in its own right, connected with other countries of British origin such as Canada, Australia, South Africa and India. Brasch was an exacting and even fussy editor, often insisting on detailed revision from his contributors, not all of whom appreciated his meticulous solicitude.

He nevertheless maintained high standards and there was little of genuine literary value written in New Zealand in the two decades of his editorship that he did not recognise and support. He put together Landfall Country: Work from Landfall 1947–61 (Caxton, 1962), a substantial anthology of the better contributions in poetry, short stories and essays. It also included twenty-nine pages of selections from the high-toned editorial Notes, which he contributed to every number.

Meanwhile Brasch continued to write poetry, publishing with Caxton The Estate and Other Poems (1957) and Ambulando (1964). The Estate was dominated by the long, uneven, personal and philosophical title-poem in thirty-four sections dedicated to the memory of his close friend T.H. Scott who was killed in a climbing accident. The shorter poems have proved more lasting.

Ambulando represented something of a shift in style as the final poem, ‘Cry Mercy’, made explicit: ‘Getting older, I grow more personal, / Like more, dislike more / And more intensely than ever—/ People, customs, the state, / The ghastly status quo, / And myself, black-hearted crow / In the canting off-white feathers’.

After his retirement from Landfall, Brasch had more time to devote to his own writing, publishing his fifth, largest, and most various collection, Not Far Off (Caxton, 1969). He also engaged in verse translation, publishing versions of poems from the Russian, German and Punjabi. A sixth collection, Home Ground, edited by Alan Roddick, was published posthumously by Caxton in 1974. It included the sinewy and impressive title-sequence and some exquisitely limpid lyrics written during his last illness.

Brasch’s evolution as poet from a preoccupation with issues of national identity towards broader and more personal concerns was something of a paradigm for the poets of his generation.

One less publicised aspect of Brasch’s activities was his anonymous support of New Zealand artists. Sargeson, Colin McCahon and James K. Baxter were among those who benefited from his patronage. He bequeathed his notable collection of New Zealand books and paintings to the Hocken Library. He also contributed substantially to the first residencies for writers, composers and painters, at the University of Otago. The Burns Fellowship, established from his patronage, provided crucial support for writers including Baxter, Janet Frame and Ian Cross.

Since Brasch’s death, much of his writing has appeared in collected editions. An uncompleted autobiography was published as Indirections: A Memoir 1909–47 (ed. James Bertram, 1980). This deals in great (if reticent) detail with Brasch’s life from childhood up to the time he began editing Landfall. The Universal Dance: A Selection from the Critical Prose Writings of Charles Brasch (ed. J.L. Watson, 1981) contains a selection of his Landfall Notes, and texts of various essays, reviews and lectures, including Present Company: Reflections on the Arts, a kind of artistic manifesto, originally published in 1966. Collected Poems (ed. Alan Roddick, 1984) includes the contents of all six of his collections plus a selection of unpublished and uncollected pieces ranging from poems written at school to some left unfinished at his death.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

In 1980, Charles Brasch was awarded third place for Indirections at the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Awards.

Enduring Legacy: Charles Brasch, patron, poet, collector; edited by Donald Kerr (2003). Published to coincide with the release of his papers from a 30-year embargo at the Hocken Library, this volume celebrates his life and legacy in a series of essays by writers and critics, including people who knew him. It is well illustrated with photographs of people and places, and colour reproductions of works from his art collection, which included Colin McCahon, Evelyn Page, Toss Woollaston and many other important twentieth-century New Zealand artists.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2008, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'The Early Poets'

- Charles Brasch in The Poetry Archive (U.K.), featuring audio recordings of his work