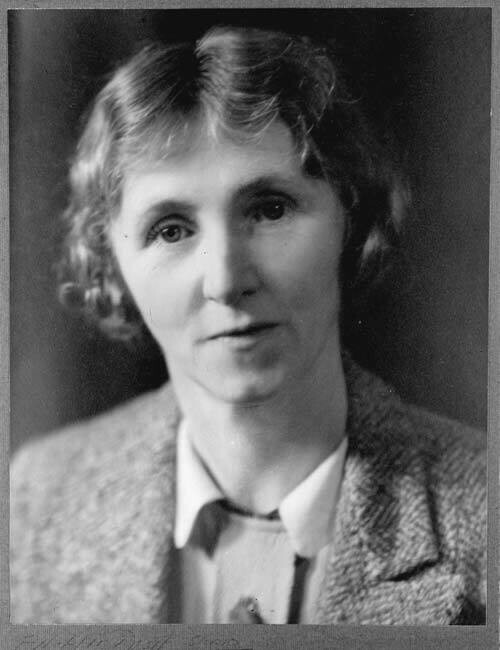

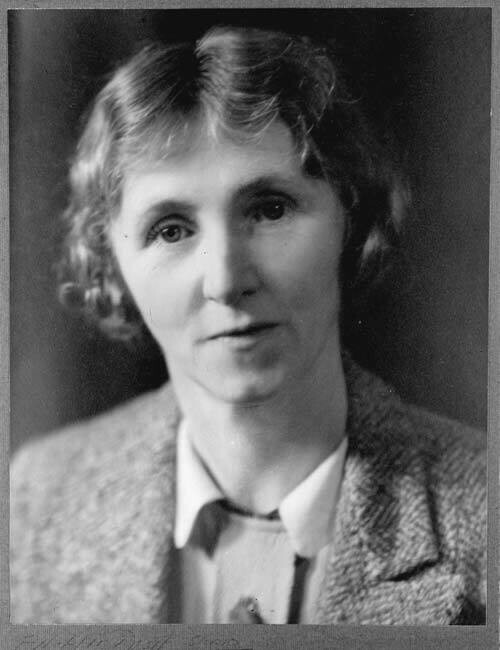

Eileen Duggan

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Duggan, Eileen (1894–1972), poet, was born in Tuamarina, Marlborough, where her parents (both emigrants from Co. Kerry) had settled in the 1880s. She attended Marlborough College and Victoria University College (MA 1918 with first class honours in history), also attending Wellington Teachers’ Training College. She taught briefly at a secondary school and later at university, but ill health forced her to abandon teaching. For almost fifty years, she earned her living solely by full-time writing—poetry, literary and historical essays, criticism and reviews, and journalism, including a regular weekly page (‘Pippa’s Page’, which she wrote for over forty years) for the Catholic newspaper, the New Zealand Tablet.

Duggan began writing poetry soon after her arrival in Wellington, and published her first volume, Poems, in 1921. Notable for its Irish content and religious interests, the volume skilfully evokes a range of emotions with an assured lyricism, already displaying her rare sense of words. It was well received in New Zealand and overseas, with a particularly favourable notice by George Russell (‘AE’). New Zealand Bird Songs in 1929 included a prefatory note describing the poems as ‘simply rhymes on their birds for the children of our country’. Some reviewers chose to ignore that, and the volume was greeted with an embarrassing level of nationalistic fervour which left her alarmed that there would be nothing left to say about the subsequent ‘real book’. Rhymes for children is an appropriate description of Bird Songs, though their skilled metrical experimentation is still of interest. The collection was very popular, and several poems proved favourite pieces for public recital or musical settings.

The first of her ‘real’ books was Poems in 1937 (American edition 1938), with an enlarged second edition in 1939, followed by New Zealand Poems in 1940, which also ran to second editions in Great Britain and America. Where her first volume had looked to the Ireland of her parents, seen at times in a romantic, Celtic light, these two focus much more attentively on the New Zealand landscape and people, and the place of the artist in a developing society. Some poems are overtly nationalistic (the cover of New Zealand Poems reads ‘In Honour of the Centennial of the Dominion of New Zealand’), and too often these are spoiled by a forced and uncomfortable rhetoric, or indulgence in fanciful imagery employed for its own sake. Other pieces are more successful, such as the simple ballads which she called her ‘peasant poems’, and the personal lyrics which are firmly tied to a vividly realised landscape, whether remembered from childhood, or known as part of her adult life. The situation of the poet in New Zealand and the nature of poetic inspiration are important themes. Her sense of the isolation of the poet (heightened perhaps by her rather secluded lifestyle) and her insistence on the primacy of an intuitive inspiration show the influence of the Romantic tradition, but the way she links poetic creativity with religious experience derives more from seventeenth-century religious poetry. Both these volumes were given a highly favourable reception by local and overseas reviewers (particularly in the United States), and for a number of years Eileen Duggan was the best-known and most widely admired of New Zealand poets. Her preference for traditional forms and for simple lyric, making often original use of the Georgian tradition, made her a genuinely popular writer, and she received national and international honours.

The publication of More Poems in 1951 signalled a significant change, both in subject and in style. Like many of her contemporaries, Duggan was deeply affected by World War 2, and by the even more oppressive threat of atomic warfare. The poems of this volume mingle shock and pity as they attempt to understand the condition of that world, but still include a spirit of hope which affirms the value of fallen humanity. The writing is spare and austere, combining passion with intelligence in a way that is reminiscent of metaphysical poetry. There is some straining to handle the prophetic role that she has adopted, and there is still at times a slightly indulgent imagery, but More Poems is Eileen Duggan’s most mature and accomplished writing.

Since New Zealand Poems, however, her reputation had seriously declined, victim to changing fashions in poetry and to the conscious reshaping of the canon of New Zealand poetry. She was absent from the Allen Curnow’s influential Caxton Press anthologies of 1945 and 1951, and from the Penguin anthology of 1960, refusing permission to be represented by a selection of which she did not approve. Her refusal seems hardly surprising given Curnow’s opinion expressed in the 1945 book that in her verse ‘the whole effect is that of an emotional cliché’.

Duggan had been prominently associated with Kowhai Gold (1930), an anthology that later came to stand for the worst excesses of Georgianism, romantic prettiness, and false play with Maori words as if they were ‘new toys’. Duggan’s reputation suffered from the attacks on Kowhai Gold and C.A. Marris’s New Zealand Best Poems (1932–43), though later critics have often exempted her from their censures of New Zealand Georgianism.

Ironically, she had written about the dangers of striving too hard to be ‘indigenous’, and had been aware of the risks since at least the mid-1920s. Her rejection of a modernist poetic came not from ignorance but from a deliberate criticism of its obscurity and formlessness. Undoubtedly, she is guilty of some of the Georgian weaknesses, but she writes with the strengths of that tradition and is never confined by it. Although her poetry prefers the generalising sentiment to the directly personal, it does spring from personal experiences which she treats in a subtly allusive manner, belying the conventional decorous exterior of the lyric form.

By the end of her career, Duggan had moved to a more sombre focus on the moral dimensions of human actions—what she wrote of as ‘the discipline of consequences’. And correspondingly her verse lost some of its fanciful imagery and indulgent language and became itself more disciplined in style, and more conscious in its subject matter of the sadness of the post-war age. Her religious faith always formed a vital part of her poetic vision. Its beliefs and values, its legends and symbols inform much of her writing, and they, as much as any personal experience, give her poetry its concreteness and intimacy, characterising her as a lyricist whose immediate forerunners may be Georgian, but who writes at the same time within a much longer and more comprehensive tradition of religious poetry. PW

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2008, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'The Early Poets'