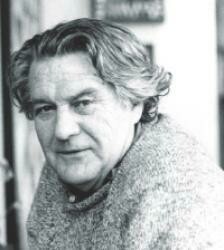

Louis Johnson

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Johnson, Louis (1924–88), Wellington poet (‘a doll-sized city . . . how many capitals are so human?'), had many volumes of verse published over a period of forty-five years. His first work appeared in 1945 and his posthumous last poems in 1990. His constant themes include suburbia, domestic life, childhood, love (with its attendant lust) and the folly of the contemporary world. His early poems, while energetic, had a tendency to vagueness and a lack of centrality, but his later much more controlled poems have been considerably underestimated. Throughout his life he spent considerable time fostering young or neglected poets; indeed, his own poetry probably suffered from his generous spirit and support for other writers.

His poetry books include Stanza and Scene (1945), The Sun Among Ruins (1951), The Dark Glass (1955), Poems Unpleasant (with James K. Baxter and Anton Vogt) (1955), Two Poems (1956), New Worlds for Old (1957), The Night Shift: Poems on Aspects of Love (with Baxter, Charles Doyle and Kendrick Smithyman) (1957), Bread and a Pension: Selected Poems (1964), Land Like a Lizard: New Guinea Poems (1970), Onion (1972), Selected Poems (1972), Fires and Patterns (1975), Coming & Going (1982), Winter Apples (1984), True Confessions of the Last Cannibal (1986) and Last Poems (1990).

In his youth, Johnson was at the centre of the ‘Wellington group’—so-called because the group defined itself in reaction to their perception of Auckland-based Allen Curnow. Accordingly its interests were claimed to be what his were not—less concern about physical landscape and the New Zealand identity, more about universal issues which transcend borders. As a group they—and particularly Johnson—wrote about actual life, society and the city suburbs with their state houses and backyard vegetable gardens. In retrospect the dispute was personal, regional and intergenerational rather than ideological. Later, Johnson himself wrote about early European exploration, envisaging Young Nick reminiscing about ‘the lost / islands of Tasman uplifted high into further murdering’.

In 1951 Johnson established the New Zealand Poetry Yearbook. He edited it annually until 1964, when Literary Fund support was withheld—with a resultant furore—on the grounds that six of the poems he had chosen were obscene. It was his policy to encourage unknown writers as well as including established poets. This catholic policy led to criticism about standards, a charge led by Curnow. Johnson, allied with Baxter, thus challenged the supremacy of the old master on two fronts. The dispute turned nasty, Curnow’s caustic comments (especially in Here & Now) leading to Johnson’s bitter irreverent replies.

Nevertheless, a considerable number of budding writers were published, and many continued writing. Johnson deserves full credit for encouraging others as well as for his own accomplishment in poetry. Throughout these years he continued to write prolifically, which he combined with editing the quarterly Numbers, running the Capricorn Press, and frequent reviewing and broadcasting.

In 1968 he moved to Papua New Guinea, and a year later to Melbourne, where he worked as a journalist. In 1971 he took a tertiary teaching position at Bathhurst, returning to New Zealand in 1980 as the second Victoria University writing fellow. Settling on the Kapiti coast, he became active again in literary politics, becoming president of PEN, as well as starting his own press, Antipodes. Through this he published Antipodes: New Writing (1987), like the old Yearbook a generous and practical shopfront for rising writers. This time, however, he included prose. His introduction says ‘literary journals and miscellanies take the pulse of the literary life as it develops and endures around us. They are closer to gossip than history and therefore more interesting. History may awe and shape us, but it’s the gossip and the daily tucker that enable us to endure it.’ He died in 1988 in England having just completed a year as Katherine Mansfield Memorial Fellow at Menton. His wife Cecilia established the Louis Johnson New Writers Award to continue his encouragement of developing talent.

Johnson’s poems are often a tentative reverie, speculations about the nature of reality. Common images are windows and mirrors, openings onto and reflections on experience and being. ‘Words are bricks you throw into every discussion / hoping to break a window, make a mark / in the nervous system of identity.’ He was a strongly moral man, angry at injustice, critical of the smug and self-satisfied, but with a well-cultivated sense of humour. His poems reflect his consciousness of the absurdity of human behaviour, while the romantic in him saw the transitory nature of existence, as well as the futility of action. ‘Let me not think of these / cruel facts of life in this valley of green trees.’ And near the end, ‘A point of view; a domestic art—meals / on the table and a warm bed. We do not need large events; / a sense of history clamping its jaws.’

As his style is discursive, a raconteur’s approach, the reader is rarely conscious of poetic form. The argument is usually all. In his early poems this was advanced by affirmation and anger; later there was a more perceptive acceptance and wry humour. In this period, his poems grounded in his new family are as good as any New Zealand poetry on this theme: his children’s pets, his son awe-struck before an elephant, his daughter learning to read, welcoming him home, delivering make-believe letters. ‘All / of it is there, all of it with you, shimmering: / a music: memory: the woman / the soft curled limbs of the children.’ ‘The Last Cannibal’, a poetic persona created by Johnson in a memorable sequence, presents a forceful later public face: ‘Memory is as rich as gravy.’ This authoritative assurance is illustrated even more clearly by the domestic poems in which Johnson re-explores early themes. ‘I tell myself / that love is quite as extreme as any entrance or exit, and does not come too late’. In these and similar poems he traverses and dissects with confidence and skill the issues of being human in the modern world. ‘Change has indeed come. / They console themselves, between one suburb / of the global village and others. / The road-houses serve blander plastic steaks: their sons / commute to bread in the dying days of Ford.’

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- Te Ara entry

- Louis Johnson discusses poetry (recording)

- NZETC

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File