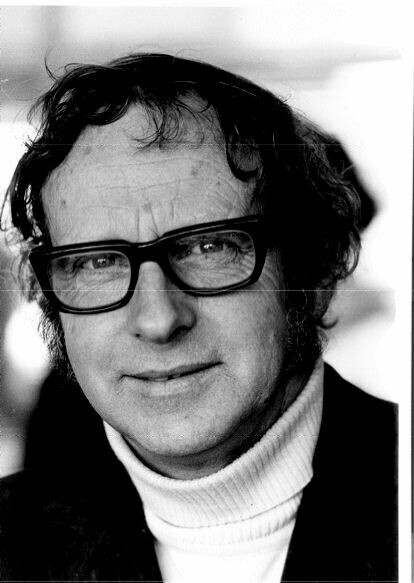

Bruce Mason

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

MASON, Bruce (1921–82), playwright, critic, fiction writer, was born in Wellington, moving at age 5 to Takapuna, where his experiences formed the basis of his most famous work, The End of the Golden Weather. He graduated (BA 1945) from Victoria University College, where he was active in drama and in the literary magazine Hilltop.

After service with the New Zealand Army 1941–43, and the Naval Volunteer Reserve 1943–45, he married Diana Shaw, a Wellington obstetrician, who continues to promote his work. From 1951 to 1957 Mason was senior public relations officer for the New Zealand Forest Service. From 1960 to 1961 he was editor of the Māori news magazine Te Ao Hou, where he challenged his readers to ask, ‘since I am a Māori, what part do I want it to play in my life?’ A leading force in founding New Zealand’s first professional theatre, Downstage, in Wellington in 1964, he was also music critic with a weekly column ‘Music on the Air’ for NZ Listener 1964–69, theatre critic for the Wellington newspapers, the Dominion 1958–60 and 1973–80, and Evening Post 1980–82), and editor of Act magazine 1967–70. He was awarded an honorary degree by Victoria University in 1977 and a CBE in 1980, and in 1996 the Bruce Mason Theatre was opened on the North Shore.

In his first major success, The Pohutukawa Tree (1960, revised 1963, first performed by the New Zealand Players Theatre Workshop in Wellington in 1957, and produced on BBC TV in 1959), Mason critiqued both Pākehā and Māori societies. In the following decade he created what for a time he called ‘Te Hoe Pakaru / The Broken Gourd’, but later published as The Healing Arch (1987). This is a cycle of five plays which focus on Māori culture since European contact: Hongi (1968, published 1974) (the clash of religions); The Pohutukawa Tree (the Māori in exile); The Hand on the Rail (1967) (the Māori in the city); Swan Song (1967) (the Māori returning to his roots); Awatea (1969) (creating a modern Māori myth). These go beyond a social history of Māoridom where individuals are alienated from their culture; in the lineaments of Greek tragedy, they show the universal pain of children alienated from parents and vice versa. Awatea, the last play in the sequence, was Mason’s ‘greatest single success’. Recorded for radio in 1965 by Inia Te Wiata and the cast of Porgy and Bess (the New Zealand Opera Company), it is a simple story of unmasking youthful deception, but shows how (in the stage direction) ‘everywhere in their lives, Māori and European rituals are mixed without incongruity’. When the Māori hero Matt resolves to become a writer at the end of the play, Mason (as he put it) ‘symbolically retired from the field’, having encouraged Māori culture tirelessly at a time when it was unfashionable to do so. A powerful revival directed by Mervyn Thompson [Author] was the highlight of cultural events organised in conjunction with the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch.

Māori culture also gave Mason a perspective from which to scrutinise his own. His critique of Pākehā society asks, ‘What kind of a society can develop under corrugated iron?’ It began with The Evening Paper (1953), one of a domestic quartet of plays. The others were The Bonds of Love (1953), The Verdict (1955) and The Light Enlarging (1963). In 1965 The Evening Paper was the NZ Broadcasting Corporation’s first TV play. Mason described it as ‘a sour little piece’ about a New Zealander returning from overseas to a stifling suburban life. While Birds in the Wilderness (1957) shows how New Zealand society crushes a different immigrant culture, and We Don’t Want Your Sort Here (1963) is a revue which satirises New Zealand’s jingoism, Zero Inn (1970) is more hopeful in the way that at least the female parental figure is converted by a dropped-out, dope-smoking youth.

Mason’s works of solo theatre were collected as Bruce Mason Solo (1981), comprising ‘The End of the Golden Weather’ (first performed in 1959), ‘Not Christmas, but Guy Fawkes’ (1976), ‘To Russia, with Love’ (1965)— the first half of The Counsels of the Wood—and ‘Courting Blackbird’ (1976). To read them together is to appreciate how Mason longed for a larger life than he saw possible in his society, or in the equally repressed and repressive Russian society in which he took an informed interest, with its ‘Petrouchkas. Stuffed men. Straw.’ (He gave a memorable valedictory lecture at Victoria University on the death of Vladimir Nabokov in 1977.) In his thirty-fourth and last play, Blood of the Lamb (1981), he skilfully combines Māori and Pākehā cultural traditions in a story which reverses Mason’s typical protagonists to make the parental generation the self-made rebels, and the child (Victoria) the force of conservatism. This ‘three-part invention in homage to W.A. Mozart and G.B. Shaw’, proudly insisting on its New Zealand setting, focuses on a lesbian couple whose feminism cuts across all macho cultures, both European (aggressive, ‘a bloody charnel-house’ where the male secretly desires the male) and Māori (‘the Māori world is a male chauvinist pigsty’).

In Theatre in Danger, an exchange of letters with John Pocock (1957), Mason discussed the art of the theatre. He always had a strong musical sense of overarching structure, ‘the totality’ of a play’s theme, and spent his life searching for workable dramatic shapes ‘in a country which will admit only games as viable rituals’. All his works, including his fiction, draw on such literary models as Sophocles’ Greece, O’Casey’s Ireland, Faulkner’s South, or Chekhov’s and Nabokov’s Russia, to articulate and mythologise a dull, parochial landscape. He deliberately places his local and often Māori themes in the aesthetic conventions of European theatre, so that (as he puts it) ‘they become bi-cultural exercises’. Like Bernard Shaw, Mason mingled sophisticated artistic intertextuality with political activism, because he always believed in the galvanising social function of theatre, especially amateur theatre. In New Zealand Drama: A Parade of Forms and a History (1973) he argued from the point of view of McLuhan and cultural studies that in the amateur theatre ‘the information chaos of the media can be transcended and made sense of’. His own oeuvre covers the genres of fiction, poetry, theatre, radio, television and journalism. Only opera is missing, although many of his plays (Awatea, Swan Song, Blood of the Lamb) are highly operatic. Mason’s analysis of Māori culture in Hongi and elsewhere is informed by ideas of media—the Europeans asked the Māori ‘totally to restructure their sensory lives, from the modes of aural resonance, to the abstractly visual’—and this leaves the new generations without even an access to a sustaining mythology.

His best-known works are decidedly undramatic, involving long sections of storytelling, although these are punctuated by set pieces of grand ritual such as a wedding or homecoming. His solo works are predominantly narrative, too. The challenge is, for the imagined listener on stage—old or young—and always for the audience, to reject or embrace the ‘myth’ that is being created before them. The plays exhort us consciously and energetically to choose a culture and live in it; the last words of his book on New Zealand drama are ‘What exactly is Māoritanga?’ He translated Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard for radio in 1960 (it was later staged in 1981) because it focuses on a group of people who don’t have the courage to make this choice. To read just some of his journalism, collected in Every Kind of Weather (1986), is to see how Mason tried to make his concerns a matter of public debate, working tirelessly in all the media to reach all New Zealanders. In many ways, he was himself a ‘made man’, who created, among his many other myths, the myth of himself. Mervyn Thompson called him ‘a Don Quixote tilting away at a landscape that doesn’t quite live up to his heroic aspirations’. Highly cultured and literate, he nevertheless longed to make contact with the ‘average New Zealander’, and did so in the inexhaustible performances of The End of the Golden Weather. As he puts it, recalling his Takapuna childhood in his monologue Not Christmas, but Guy Fawkes, ‘I in my flaxbush and the people on the lawn, form a context: if I could not communicate with them, it was because they refused communication with me, or the likes of me. And the reasons for this refusal have become the mainspring of my work.’

Mason was therefore fascinated by ‘mid-racial’ people who fit in neither culture. In Swan Song the hero is a Māori opera lover now learning Māoritanga, and in The Pohutukawa Tree Johnny is possessed by the myth of Robin Hood. This interest extends to his work with European settings, such as the German officer in The Waters of Silence (1965), or Dmitri in its companion piece To Russia With Love. His works often focus on sensitive individuals trying to create personae to satisfy a culture’s or elder’s demands, but being either unmasked or proved unequal to the role. The sympathy at that point is usually with the individual and against the crucifying society, whether Māori or Pākehā, capitalist or communist. In his life and art, Mason never lost an optimism that one day people would sort out their allegiances. Blood of the Lamb is therefore the fitting climax to his career: its exuberant heroines are citizens of the world yet thoroughly embedded in and committed to their local culture. When the daughter Victoria awkwardly accepts their unorthodox behaviour and roles in her life, Eliza observes, ‘Well, I guess that’s the most we can expect from this time and clime.’ While Aroha dies at the end of The Pohutukawa Tree, and Matt only sketchily promises to become a Māori writer at the end of Awatea (Mason attempted to fill in this sketchiness in 1978 when he published some letters purportedly written by Matt), Eliza’s understatement is the first firm stone laid by Mason in building his longed-for healing arch.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File

- Bruce Mason's Playmarket profile