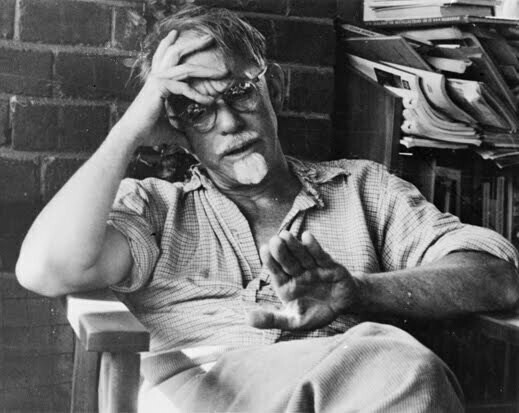

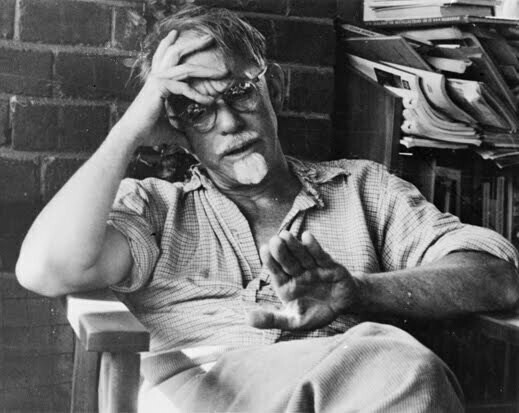

Frank Sargeson

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Sargeson, Frank (1903–82), was born Norris Frank Davey, the child of a middle-class family in Hamilton. He was educated there and in Auckland until he completed his training as a solicitor in 1926, when he went for two years to Britain and Europe. Returning in 1928, he decided not to pursue a career in law and instead worked at various jobs before settling on family land near Takapuna, where he was to remain for the rest of his life, most of it as a full-time writer.

He had begun writing in the late 1920s, but did not establish a significant reputation until he began to contribute short sketches and stories to the radical periodical Tomorrow from 1935. First collected as Conversation with My Uncle, and Other Sketches (1936), these saw Sargeson beginning to master the elements that over the next twenty years were to become the distinctive features of his style: an economic delineation of character, minimalist narration, and an understanding of the tight range of idiomatic vocabulary and syntax appropriate to his characters.

Sargeson published forty stories between 1936 and 1954, all but two completed by 1945. Most were collected in Conversation with My Uncle or in two later volumes, A Man and His Wife (1940), and That Summer, and Other Stories (1946). ‘The Making of a New Zealander’ was adjudged joint winner in the short story section of the 1940 Centennial Literary Competition. In these years Sargeson dominated New Zealand short fiction.

The stories, showing some indebtedness to Sherwood Anderson and Hemingway, are frequently wry sketches or ostensible yarns about apparently undistinguished characters and minor occurrences. The background, explicit or implied, is New Zealand in the years between the two World Wars, and particularly the 1930s Depression, against which the characters are depicted as itinerant labourers or unemployed men, seldom happily married and frequently without any apparent family connection.

The stories drew praise for their social realism and austere economy of language, appropriate to the apparently unimaginative principal characters who were often the semi-articulate narrators and chroniclers of the events. The narrators’ starkly limited point of view characterises a view of the world that dare not admit openly the emptiness and loneliness that is immanent. This was accepted as true of the limited, puritanical, emotionally sterile world of the New Zealand working-class male, isolated by gender, economic status and emotional incapacity, relying on the unspoken expectations of ‘mateship’ for some partial fulfilment that more often than not proved elusive. More than any other works before them, Sargeson’s stories captured working-class New Zealand vernacular, the society that gave rise to it and much of its inner spirit.

In 1945 Sargeson published the first part of a novel-in-progress under the title When the Wind Blows. The complete novel, a study of youth and self-discovery, was I Saw in My Dream (1949), published in England by John Lehmann, who had published earlier work by Sargeson in the wartime Penguin New Writing, and the That Summer collection. But the small collection by New Zealand writers which Sargeson edited as Speaking for Ourselves in 1945 pointed towards post-war roles of mentor to younger writers such as Maurice Duggan, John Reece Cole and Janet Frame, confidant of contemporaries such as Roderick Finlayson and E.H. McCormick, and collaborator with arbiters of taste, such as Dan Davin, in the influential 1953 World’s Classics selection of New Zealand short stories for Oxford University Press.

As writer, however, the post-war years were less fruitful for Sargeson than he had hoped. Though sixteen New Zealand writers were to hail his fiftieth birthday with a letter of congratulation and appreciation in Landfall (March 1953), the decade that followed was not productive. He published one novella (I For One), two stories and a short essay in autobiography; a pair of plays were only partially completed, and a novel presented continuing difficulties.

But in his sixties Sargeson enjoyed a remarkable new burst of creative achievement. In 1964 the first complete collection of his stories was published, with a thoughtful introductory essay by Bill Pearson. In 1965 the two plays, ‘A Time for Sowing’ and ‘The Cradle and the Egg’, were published under the collective title of Wrestling with the Angel, and in the same year the novel Memoirs of a Peon appeared.

This work, together with its two successors and the half-dozen short stories written before 1970, would establish a new narrative technique through which Sargeson explored a different kind of character, in a world of mostly dark comedy. The characters of Sargeson’s later fiction are principally middle-class. In place of the old inarticulate minimalism, the narration is frequently ornate, even verbose, and often expansive, reminiscent of eighteenth-century formalism. The narrators themselves, whether authorial or identified with a character, are now more articulate, much more confident with language. Yet for all their fluency, they reveal themselves to be no less isolated, no less puritanically constrained, no less ultimately defeated, than their hesitant predecessors.

Each of the three later novels is close to dark farce or tragicomedy. In each, the protagonist is left at the end surrounded by images of failure rather than success, with his ambitions achieved at a price that is at best pyrrhic and at worst shocking. In Memoirs of a Peon the Casanova-character Michael Newhouse pursues his erotic and commercial ambitions through the stifling world of 1920s provincial New Zealand until a predictable miscalculation and retribution leaves him wryly observing a seemingly inevitable fate. The Hangover (1967), possibly its author’s favourite, describes the dark fall into homicidal frenzy of a young university student, trapped between the puritanical and potentially incestuous ambitions of his overweening widowed mother, and a nether-world of social and sexual grotesques in 1960s ‘Bohemian’ Auckland.

Joy of the Worm (1969) owes much to Smollett in its style, but also something to Butler’s The Way of All Flesh in its subject matter. Its protagonists, the Reverend James Bohun and his son Jeremy, compete intellectually and sexually for the domination of their respective partners, and by extension, of each other, until, having destroyed the women they are supposed to have cherished, they strike a bargain in the nature of a truce and move laconically towards retirement, each in his own eccentric way.

There is much irony but little real laughter in these novels, and the sombre tones are carried into the several novellas that Sargeson wrote in his last years. He had attempted the form in ‘That Summer’, the centrepiece of the stories written prior to 1945, and developed it in I For One. He reprinted this in 1972 together with two other stories, ‘A Game of Hide and Seek’ and ‘Man of England Now’, the latter giving the 1972 volume its title. Here Sargeson offers his reader studies of the grotesques that figure increasingly in his repertoire of characters from The Hangover on. The tendency to emphasise not merely the unorthodox but the thoroughly bizarre is present in stories of the 1960s such as ‘Charity Begins at Home’ and ‘An International Occasion’. In the last four or five novellas, it became a staple of the fiction.

In his seventies, however, Sargeson returned to the subjective but essentially naturalistic style of more orthodox narrative as he composed a trilogy of memoirs. Much earlier, he had written an autobiographical essay entitled ‘Up onto the Roof and Down Again’ forCharles Brasch who published it in four parts in Landfall between December 1950 and December 1951. Expanded to more than twice the original length with the addition of a memoir called ‘Third Class Country’ recalling the farm of his uncle Oakley Sargeson, the two pieces were published as one volume of autobiography under the title Once is Enough in 1973.

The two volumes that followed, More than Enough (1975) and Never Enough (1977), trace Sargeson’s life as a writer discursively but more or less sequentially from the 1930s to the 1970s. They are rich in anecdote, reminiscence and insights into both his life and creativity. The trilogy of autobiographies therefore stands as an important document in the history of New Zealand writing. They were published as one volume, Sargeson, in 1981.

Sargeson’s last published short story was ‘Making Father Pay’, in the NZ Listener, 7 June 1975. His last two novellas were Sunset Village (1976), a comic crime mystery story set in a geriatric community, and En Route, the story of a journey of discovery made by two feminists in middle life, published together with a novella by Edith Campion in a joint volume entitled Tandem (1979).

In 1978 his seventy-fifth birthday was commemorated with a 360-page* issue of the periodical Islands (issue 21) containing reminiscences by friends, evaluations and commentary, and excerpts reprinted from his earlier work. His own critical writing, reviewing and essays were collected in Conversation in a Train and Other Critical Writing, edited by Kevin Cunningham in 1983.

Frank Sargeson was undoubtedly the most important New Zealand writer of short fiction in the years following the death of Katherine Mansfield. Like her, his reputation helped promote the recognition of New Zealand writing beyond the country’s shores. Unlike her, he wrote his major works during a lifetime’s residence in New Zealand.

He focused relentlessly on his male characters and their experiences in a spiritually depressed society, exploring subjects and themes which appeared to him to necessitate an austere style that eschewed the apparently imaginative in favour of a harsh and pessimistic social realism. The romantic and homoerotic subtexts which the contemporary reader discerns suggest that Sargeson’s narratives are more than just the social realist fictional records of a section of society, as an earlier generation largely saw him. His work has survived his generation, and he remains a major figure for his achievement and influence in New Zealand fiction.

In 1995 Michael King published a biography of Sargeson distinguished for its detailed research and for establishing that Sargeson’s withdrawal from the public life of a lawyer, and his change of name, were consequential on homosexual activity. The reception of King’s book also reaffirmed Sargeson’s continuing significance as a reference point in literature.

WB

* Correction: the number of pages is 150.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

A new edition of the short stories by Frank Sargeson, with an introduction by Janet Wilson, was published by Cape Catley Ltd (2010). This collection includes some early works which have not previously appeared in Sargeson collections.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Librarys New Zealand Literature File.

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2008, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'Early Male Prose Writers'.