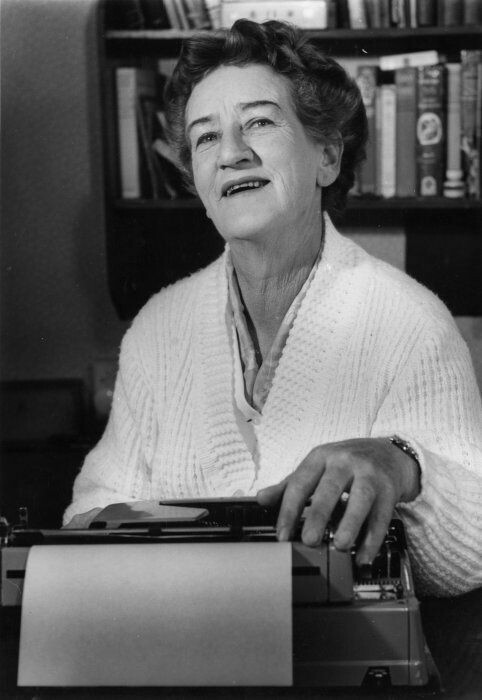

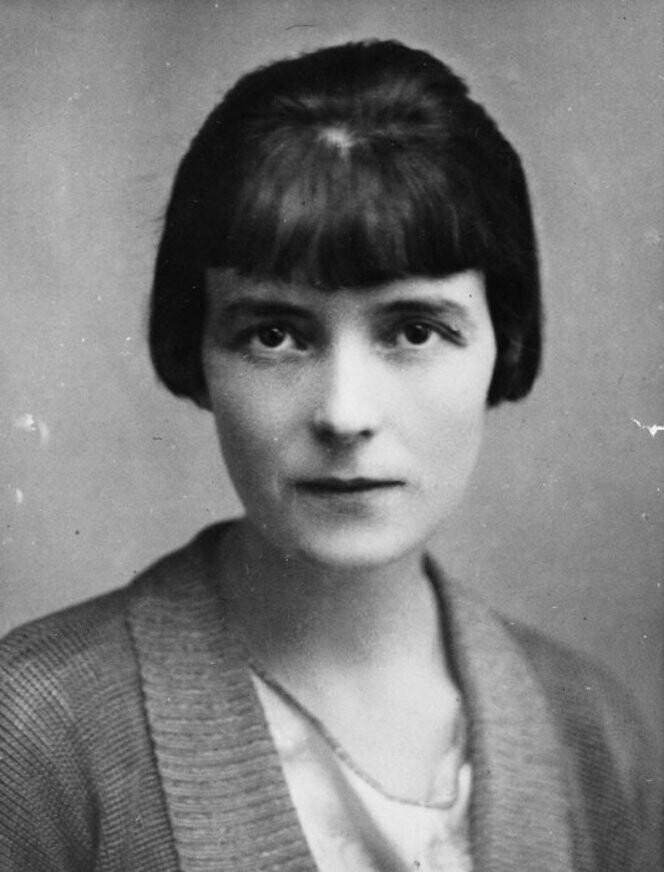

Katherine Mansfield

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

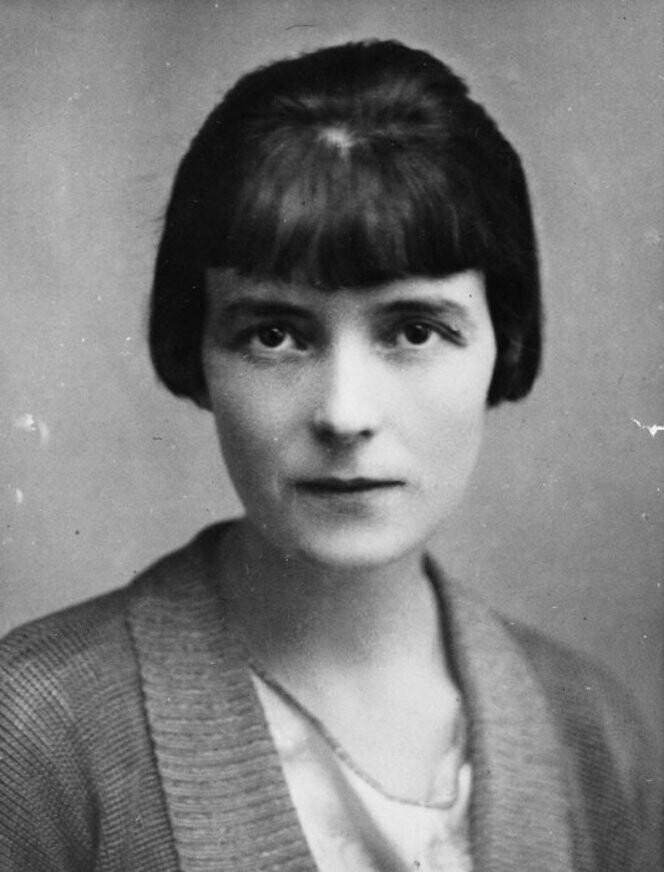

MANSFIELD, Katherine (1888–1923), was born in Wellington as Kathleen Mansfield Beauchamp, into a family with vigorous social ambitions. Her mother was the delicate and aloof Annie Dyer; her father, Harold Beauchamp, a canny and successful businessman. A first cousin in Sydney became the best-selling novelist, and Mansfield’s first role model, Elizabeth von Arnim.

Mansfield’s early school years were spent in Karori, a village in the hills a few miles from Wellington, until the Beauchamps returned to Wellington, to an impressive merchant’s mansion and a more select social programme, when she was 11. At first she attended Wellington GC, then Miss Swainson’s private school. In 1903 Beauchamp, now director of the Bank of New Zealand, chose Queen’s College, Harley Street, London, an institution founded by Charles Kingsley for the liberal education of women, to add metropolitan polish to his clever and handsome daughter. She immersed herself in French, German and music, and began writing sketches and prose poems. In the Queen’s College Magazine she published ‘About Pat’, her first re-creation of childhood in Karori, written in direct and simple prose, as well as ‘Die Einsame’, redolent with fin-de-siècle motifs and symboliste elaboration of mood. The New Zealander and the European had begun their never quite resolved engagement.

Kathleen Beauchamp returned to Wellington, rebellious and unsettled, in late 1906. Although her life was comfortable and socially expansive, for the next twenty months she warred against parental vigilance, and found Wellington understandably provincial. She filled what she later called ‘great complaining notebooks’, published her first work under noms de plume in The Lone Hand and The Native Companion in Australia, and moved through a number of furtive infatuations with men and women. She also made an extended caravan journey into remote Urewera country in the middle of the North Island, her one experience of ‘roughing it’, returning home with a liking for Maori and English tourists, ‘but nothing in between’. Her father accepted her plea for musical training in England and she arrived again in London in August 1908, ‘Katherine Mansfield’ already decided on as her pen-name.

Within weeks life was, as she had hoped, complex and sophisticated. She was in love with Garnet Trowell, a young violinist whose father had taught her the cello in Wellington. When the affair collapsed some months later, she impulsively married G.C. Bowden, a singing teacher whose name she officially bore for the next nine years, but whom she left the day after the marriage. She returned to Garnet, travelled with his opera company, became pregnant, and again separated. During those months she depended, as she was to do for the rest of her life, on her close but exasperating friendship with Ida Baker, her Rhodesian school chum from Queen’s College. Usually referred to as L.M. (‘Leslie Moore’) or Jones, she was also variously nicknamed over the years as the Albatross, the Cornish Pasty, the Faithful One. A coldly efficient Annie Beauchamp, wrongly suspecting an ‘unhealthy’ friendship with Ida, arrived from New Zealand to install her daughter at Wörishofen, Bavaria, hoping that the famous water cure might restore normality.

After the birth of a stillborn child, Mansfield stayed on in Germany until the next January. She formed a liaison of sorts with the Polish translator, journalist and con-man, Florian Sobienowski. Later he would attempt to blackmail her with letters she wrote at this time, but he encouraged her to read Russian writers, especially Chekhov, and was indirectly responsible for her finest poem, ‘To Stanislaw Wyspiansky’. Ostensibly a tribute to a Polish patriot and poet, it prompted her to consider her own country, ‘Making its own history, slowly and clumsily / Piecing together this and that, finding the pattern, solving the problem, / Like a child with a box of bricks’ and remarking of herself, with a Whitmanesque bravura, ‘I, a woman, with the taint of the pioneer in my blood’.

The months in Bavaria also provided the occasion for the satirical stories she began contributing to A.R. Orage’s journal, the New Age, once she was back in England. The stories spared neither Germans nor family life, and presented sex, pregnancy and social divisions with almost ferocious candour. These New Age stories, and a number of others, were collected in 1911 as In a German Pension. As well as presenting her as a fresh and incisive voice, Mansfield’s association with the respected Fabian weekly led to a close and ultimately bitter friendship with Orage’s eccentric South African mistress, Beatrice Hastings. Still dependent on Ida Baker’s homely loyalty, but drawn to the modish insouciance of her new literary circle, Mansfield took her most decisive turn when, at the end of 1911, she met the precociously gifted, lower-middle-class Oxford undergraduate, John Middleton Murry. He was already the founding editor of Rhythm, a quarterly self-consciously dedicated to the spirit of Modernism, to Mahler in music, Post-Impressionism in art, and Bergson in philosophy, yet calling also for ‘guts and bloodiness’, an escape from both Englishness and aestheticism. It was a call that brought from Mansfield the small group of New Zealand stories that depicted the emotional and physical violence of raw colonial life. In ‘The Woman at the Store’, ‘Millie’ and ‘Ole Underwood’, she moved the popular colonial low-brow yarn towards a fresh psychological depth and an awareness of impressionist technique. Although Dan Davin excluded them from his Selected Stories (Oxford University Press, 1953) as dealing ‘with scenes she had glimpsed only superficially’, they are an essential part of her oeuvre, the first New Zealand stories to thread human behaviour with the brooding grimness of landscape. In a much-quoted sentence from ‘The Woman at the Store’, which Allen Curnow took up as epigraph to his Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse (1960), she noted ‘There is no twilight in our New Zealand days, but a curious half-hour when everything appears grotesque—it frightens—as though the savage spirit of the country walked abroad and sneered at what it saw.’

Within weeks of meeting, Mansfield and Murry had set up house together, assuming the literary role of ‘the two tigers’, and begun their habit of addressing each other as Tig and Wig. Her new allegiances drew a series of savage satirical attacks in Orage’s portrait of her as ‘Mrs Foisacre’ in the New Age. When Rhythm folded in mid-1913, she and Murry jointly edited the three issues of its successor, the Blue Review. Soon after they began an intense and troubled friendship with D.H. Lawrence and Frieda Weekley, at whose marriage they featured as official witnesses.

At the end of the same year, their attempt to set up as writers in Paris was cut short by Murry’s bankruptcy in the wake of his collapsed journals. Mansfield had written only ‘Something Childish but Very Natural’, and life back in England meant frequently changed addresses and meagre funds. Soon after the outbreak of World War 1, they moved to Great Missenden, with the Lawrences not far off, and Mansfield began her deep and lasting friendship with the Ukrainian Jew, S.S. Koteliansky. When her relationship with Murry seemed close to falling apart, she set out for Paris in early 1915, to the borrowed apartment of the French novelist, journalist and committed bohemian Francis Carco. But first she visited Carco at Gray, in the Zone des Armées where he was posted. The brief affair contributed to her war story, ‘An Indiscreet Journey’, as did Carco himself to the cynical roué, Raoul Duquette, three years later in her ‘cry against corruption’, ‘Je ne parle pas français’.

Before her return to Murry, Mansfield began in The Aloe what she hoped would be a novel based on her own family, and the move when she was a child from Tinakori Road to Karori. Memories were further revived when she met up with her beloved younger brother Leslie, who had joined a British regiment. For the Autumn issue of the Signature, a short-lived periodical put together by Murry and Lawrence, she wrote ‘The Wind Blows’, an exquisitely controlled re-creation of adolescence and the Wellington of her girlhood. But the enduring motive for a return to New Zealand settings, and her intense focusing on both memory and a new narrative technique, was the death of her brother in Belgium in October 1915. As she wrote soon after, ‘the form that I would choose has changed utterly. I feel no longer concerned with the same appearance of things.’ Two years later, when Virginia Woolf asked for a story for her Hogarth Press, Mansfield reshaped The Aloe into Prelude (1918). Now a shorter fiction in twelve discrete sections that cut and overlap in a method she derived from cinema, it ran together symbolism and realism with a vivid emotional resonance, achieving ‘that special prose’ she equated with both elegy and celebration. ‘And won’t the "Intellectuals" just hate it’, she said. ‘They’ll think it’s a New Primer for Infant Readers. Let ’em.’ She continued to mine her early memories, while also writing clever, more brittle stories, such as ‘Bliss’ and ‘Psychology’, that drew on her friendship with the Garsington and Bloomsbury ‘sets’, and allowed her the satirical stance that was also a self-protective play.

Mansfield’s friendship with the Lawrences had reached crisis point in Cornwall in mid-1916. Although she felt Lawrence’s dark spasms of rage were so close to her own temper, the ‘dear man’, as she wrote to a mutual friend, had become lost in ‘the immense german Christmas pudding which is Frieda. And with all the appetite in the world one cannot eat one’s way through Frieda to find him.’ She grew closer to Lady Ottoline Morrell and, more cautiously, to Virginia Woolf. For a time Maynard Keynes was her landlord, Lytton Strachey was attracted to her because she was like a Japanese doll, Bertrand Russell admired her mind and attempted an affair, while T.S. Eliot warned Ezra Pound she was ‘a dangerous woman’. But Mansfield’s wary colonial elusiveness allowed more relaxed friendships with artists and the mildly eccentric—for a time, with the East End painter Mark Gertler, and the androgynous Carrington; more enduringly, from 1912 onwards with the Scottish painter J.D. Fergusson, and the American Anne Estelle Rice, whose portrait of her is in the National Museum in Wellington; and increasingly with the deaf aristocrat, Dorothy Brett, who also painted. But it was illness, rather than choice, that led to her gradual separation from most of her friends in England.

From early 1918, when her tuberculosis became a matter of serious concern, Mansfield moved constantly between London and the Riviera. Even after her marriage to Murry in mid-year, she remained dependent on Ida Baker as companion and quasi-nurse, while Murry was committed to his war work in MI5, then later to his journalism. With various winterings-over in Bandol, Ospedaletti, San Remo and Menton, and summers back in Hampstead, Mansfield accumulated enough stories to put together Bliss and Other Stories (1920). In early 1919 Murry had taken over editorship of the Athenaeum and separation, reuniting, and again separation established itself as the rhythm of their lives, while there flowed between them a highly charged correspondence. Mansfield’s letters were always an amalgam of wit, joie de vivre, and direct emotional exchange. Those written to Murry took on the added poignancy of a constant but frequently tested love, with the sharp tracing of her illness in the recurring sequence of elation as she first moved, regret and confusion while they were apart, then restored delight. Her vivacity and frankness as a correspondent increasingly prompts critics to value her letters as highly as her fiction. Taken with her numerous notebooks, they offer a richly detailed account of a modern woman’s engagement with love, art, solitude, impending death and war. ‘The war is in all of us,’ she wrote, even after hostilities were over, as she increasingly drew an analogy between the corruptions of civilisation and her own physical decay.

The most fruitful period in Mansfield’s creative life began when she rented the Villa Isola Bella in Menton in September 1920. In the previous eighteen months, much of her energy had gone into almost weekly reviews for the Athenaeum, and translations of Chekhov’s letters, in collaboration with her friend Koteliansky. Although diverting and astute, she seldom had the chance in her reviews to discuss any but inferior fiction. She was now determined to concentrate on her own work—‘they are already chopping down the cherry trees’, as she wrote in her awareness of limited time. At Menton she wrote the bitter and posthumously published ‘Poison’, touching again on the tensions of her marriage, but also the compassionate ‘Miss Brill’ and ‘The Stranger’, and ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’, which attracted critical acclaim and the admiration of Thomas Hardy, when published in the London Mercury in May 1921. That same month Mansfield left for Switzerland, where she and Murry, who had resigned from the Athenaeum, took a chalet at Montana-sur-Sierre. She worked diligently to produce made-to-measure stories for the high fees paid by the Sphere, but also some of her strongest New Zealand stories—‘I long, above everything else, to write about family love.’ Returning to the characters of Prelude, and her own projection as the child Kezia, she wrote ‘At the Bay’, as well as ‘Her First Ball’, ‘The Garden Party’, ‘The Doll’s House’, and in a very different key, the enigmatic and unfinished ‘A Married Man’s Story’.

Disillusioned with current medical practice, Mansfield decided on an expensive and useless X-ray treatment. The move to Paris early in 1922 brought her into the circle of Russian emigré intellectuals, while her own reading of Ouspensky, her conviction that she must now ‘risk anything’, and the renewed influence of her early mentor Orage, led her to seek a cure that was spiritual as much as physical. She wrote little in Paris, but early in the year produced ‘The Fly’, her classic final statement on war, futility and courage, and the last of her many attempts to depict her father. In her final story ‘The Canary’, the image of the singing and ailing bird is to some extent a representation of herself and the limitations of her own writing, a low-key elegy in which grief becomes acceptance and, ultimately, mystery.

After a brief return to Sierre, and two months in London, in October Mansfield entered the Gurdjieff Institute for Harmonious Development at Fontainebleau. Commentators and biographers remain troubled by her decision to place herself under the direction of a guru who is often presented unsympathetically, and to live in a commune of Russians and truth-seekers—‘my people at last’, as she called them. Although Gurdjieff treated her kindly, she was by no means a disciple. Her quest was very much along personal lines, a movement against what she regarded as the crippling intellectualism of post-war European life. In almost her last letter, she declared her goal to be total honesty. ‘If I were allowed one single cry to God, that cry would be: I want to be REAL.’ She died at Fontainebleau on 9 January 1923, a few weeks before the publication of The Garden Party and Other Stories, which confirmed her place among the Modernists of her generation.

Murry was criticised by his contemporaries, and savagely satirised in Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point (1928), for his enthusiasm in publishing his wife’s literary remains, and by later critics for his reverential management of her reputation. But our debt to him is considerable. From her uncollected and unpublished stories he produced The Doves’ Nest and Other Stories (1923) and Something Childish and Other Stories (1924). He followed these with Poems (1924), The Journal of Katherine Mansfield (1927), the two-volume The Letters of Katherine Mansfield (1928), The Aloe (1930), Novels and Novelists (1930), The Scrapbook of Katherine Mansfield (1937), Katherine Mansfield’s Letters to John Middleton Murry, 1913–1922 (1951) and a misnamed ‘Definitive Edition’ of the Journal of Katherine Mansfield (1954). There have been numerous editions and collections of Mansfield’s stories in over twenty languages, although Antony Alpers’s The Stories of Katherine Mansfield (1984) was the first scholarly edition, establishing definitive texts. A comparative text of ‘The Aloe’ with ‘Prelude’ (1982), an enlarged edition of Poems (1988) and The New Zealand Stories of Katherine Mansfield (1997) were edited by Vincent O’Sullivan. Four of the five volumes of The Collected Letters of Katherine Mansfield, edited by O’Sullivan and Margaret Scott, have appeared between 1982 and 1996. The Journals, edited by Margaret Scott, were published in two volumes in 1997. Alpers’s The Life of Katherine Mansfield (1982), successor to his ground-breaking Katherine Mansfield, A Biography (1953), remains the fullest and essential account of her life. Other biographical studies include Ruth Elvish Mantz and J.M. Murry, The Life of Katherine Mansfield (1933), Jeffrey Meyers, Katherine Mansfield (1978) and Claire Tomalin, Katherine Mansfield: A Secret Life (1987). VO

Entry on critical response by Roger Robinson

Mansfield, Katherine (2), is at best a qualified national icon in New Zealand. As an expatriate writing in the London literary world and reflecting European movements of thought she had little connection with early New Zealand writing, which accorded her little recognition. In Europe Francis Carco, John Middleton Murry and Aldous Huxley put versions of her into novels, and other accounts were published by A.R. Orage, Olgivanna, Beatrice Hastings and others. Robin Hyde caught the ambivalence of the local response in her article ‘The Great New Zealand Novel’ (1929): we ‘murmur sympathetically if vaguely "Katherine the Great". But she went far from us most of her tales were written in a subtle foreign language which is not yet fully understood out here the language of twentieth century art’. O.N. Gillespie included her in New Zealand Short Stories (1930) but observed that ‘the average New Zealander is prouder of Sir Ernest Rutherford than of Katherine Mansfield’. There was little published response, imaginative or scholarly, apart from her father Harold Beauchamp’s Recollections and Reminiscences (1937), until Pat Lawlor’s The Mystery of Maata: A Katherine Mansfield Novel (1946). D.M. Davin’s Selected Stories for Oxford University Press (1953), Antony Alpers’s first version of the life, Katherine Mansfield, a Biography (USA, 1953; UK 1954) and Joan Stevens’s discussion in New Zealand Short Stories (1968) were similarly early as treatments by New Zealand scholars.

The establishment of the Katherine Mansfield Memorial Awards in 1959 indicated growing recognition, as did the Mansfield Memorial Fellowship in 1970. Only then, fifty years after her death, did New Zealand imaginative writing begin to engage with this complex presence in the country’s cultural history (Lawlor’s book excepted). Brian McNeill’s successful play The Two Tigers (1973, publ. 1977), about the Mansfield–Murry relationship, began this process, though Pat Evison’s readings, ‘An Evening with Katherine Mansfield’ (1971, recorded 1972) were a precursor. In scholarship, Ian Gordon’s editions of the New Zealand stories, Undiscovered Country (1974) and the The Urewera Notebook (1978), were followed by editorial and critical work, by (among others) Vincent O’Sullivan, Helen McNeish, C.K. Stead, Cherry Hankin, Margaret Scott, Gillian Boddy, Lawrence Jones and Andrew Gurr, with Alpers’s revised Life (1980) and edition of the Stories (1984) the seminal books in establishing the significance and nature of Mansfield’s New Zealand identity. Michael Gifkins edited The Garden Party: Katherine Mansfield’s New Zealand Stories (1987) and Vincent O’Sullivan The New Zealand Stories of Katherine Mansfield (1997).

Cathy Downes’s solo The Case of Katherine Mansfield (1978, publ. 1995), compiled entirely from Mansfield’s words, has now been performed more than 500 times. Mansfield stories have also been adapted in New Zealand for film (The Doll’s House, dir. Rudall Hayward, 1975), television (‘The Woman at the Store’, 1974), workshop theatre (Craig Thaine, Today’s Bay, 1982, publ. 1983), ballet (‘Bliss’, Royal New Zealand Ballet, 1986), opera-drama (Peter Wells, ‘Ricordi!’, 1996), chamber-opera (Dorothy Buchanan, ‘The Woman at the Store’, libretto by Jeremy Commons, 1998) and frequently for radio, the earliest probably ‘Daughters of the Late Colonel’ in 1947 and the most important the 1988 Centennial Year series produced by Elizabeth Alley. Mansfield’s life has produced two films involving New Zealand artists, Leave All Fair, directed by John Reid (1984) and A Portrait of Katherine Mansfield: The Woman and the Writer, script by Gillian Boddy, directed by Julienne Stretton (1987).

New Zealand’s attitude to its national icons being what it is, most literary energy has gone into challenging, subverting or displacing her status. Examples of canonising, sanitising or elevating her into a literary progenitor are hard to find. Her stories and life are often now used as the starting point of updated or ‘reinscribed’ variations. Janet Frame alludes somewhat ironically to Menton and Mansfield (as ‘Margaret Rose Hurndell our famous writer’) in Living in the Maniototo (1979). Rachel McAlpine provides new angles and narrators for five stories in poems in Fancy Dress (1979). Patricia Grace indicates the cultural distance between a teacher’s adulation for ‘Kay Em’ and a Maori schoolboy’s priorities in ‘Letters from Whetu’ (The Dream Sleepers, 1980). Ian Wedde in Symmes Hole (1986) presents Mansfield largely as a figure of death and of distraction from an essentially Pacific culture.

Mansfield’s illness and death are again the dominant allusions in poems by Fleur Adcock and Marilyn Duckworth (see Landfall 172, 1989, a special Mansfield issue), and her exile, ‘an old / woman / living in Menton’, in Bob Orr’s ‘K.M.’ (in Breeze, 1991). O’Sullivan’s dark mock music-hall frolic, Jones and Jones (1988, publ. 1989), irreverently explores the Mansfield–Ida Baker relationship. Alma de Groen’s feminist play on power, The Rivers of China (1988), focuses on Mansfield’s elusive or fragmentary identity (‘You have dozens of selves, all calling themselves "Katherine Mansfield"’). Bill Manhire’s jocund title The Brain of Katherine Mansfield (1988) has more to do with the Centennial year than the book’s contents, Mansfield appearing only as another icon to mock, along with Samuel Marsden and Colin Meads. Witi Ihimaera’s Dear Miss Mansfield (1989) provides a ‘Maori response’ and equally challenging cinéma noir versions. A poem by Anne French and short story by Lloyd Jones deal less than predictably with the Menton connection. Stead in The End of the Century at the End of the World (1992) has his ‘Katya’ faking her 1923 death and returning to New Zealand, dying in the 1950s. Chris Orsman’s poem ‘Another Country’ (Ornamental Gorse, 1994) has the Mansfield said to be ‘imaginative to the point of untruth’.

And so on. No other New Zealand figure has troubled or challenged so many writers to irreverent, defiant or merely exploitative responses. Perhaps the most curious aspect is the underlying assumption that she ever has been an establishment icon. As Hyde said in 1929, ‘we’ve never exactly hung her portrait on the drawing-room wall’. Corporate sponsorship of the Award and Fellowship, and the carefully restored Birthplace (a winner of the New Zealand Tourism Award) are the only signs of this. The resistance in 1988 even to the idea of a Mansfield Centennial is discussed in a commentary in Landfall 171 (1989).

Scholars are taunted about the ‘Mansfield industry’, yet major work remains to be done. Publication of the letters is still approaching completion, the notebooks remained one of the crucial unpublished texts in modern world literature until Margaret Scott’s 1997 edition, the stories are still lacking a truly complete edition, and critical understanding is far from adequate to the work. If an icon at all, Mansfield stands for elusiveness, instability, fragmentation, incompleteness and absence. RR

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Personal effects purchased by library (30/7/01)

In 2001, The Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington purchased at a London auction a tin trunk containing a collection of letters, telegrams, photographs, albums and other items which were once the treasured possessions of the New Zealand expatriate writer Katherine Mansfield.

The papers include letters from Mansfield's younger brother, Leslie Heron Beauchamp. Written between 1913 and 1915, the letters describe the sights and smells of the children’s’ childhood in the Wellington suburb of Thorndon, as well as his hopes and dreams for the future - 'I shall occasionally take a trip to England -- anyhow shall retire from business by the time I am thirty eight or forty.'

However, it was not to be. Leslie, on active service with the South Lancashire Regiment in Flanders during the First World War, was killed accidentally in October 1915. He was 19. Included in the box are the telegrams that first informed Mansfield of his tragic death and letters from his commanding officer that better explain its circumstances. Also in the box is a photograph of Leslie’s grave, together with moss apparently gathered from it.

Most strikingly, a long lock of Mansfield's chestnut brown hair - half a metre in length, and wrapped in a linen handkerchief - was found in the box.

'This is a collection of things that were obviously deeply personal to Mansfield when she placed them for safe-keeping in this deed box,' said David Retter, Acting Curator of Manuscripts and Archives at the Alexander Turnbull Library. 'Many items held reminders of her childhood in Wellington, of the short life of her only brother and provide valuable information about her relationships with other family members.

'The collection is of great informational value to researchers and we look forward to making it available to a wider audience,' he said.

Included in the collection are a large number of photographs, both loose and in albums, some taken by family members, and some professional studio portraits. Although many of the photos have been previously published by Mansfield's husband John Middleton Murry and other creatives, some are previously unseen, thus offering fresh insights into Mansfield’s life and works. Also featured in the collection is Mansfield’s 1903-dated autograph book - a doodle- and poem- covered memento from her school days at Queen’s College, London – and a 1908 journal kept by her siblings during a holiday to Nelson and inscribed to her.

Chinese view of Mansfield (15/5/01)

A new book from the University of Otago Press gives the Chinese view of Katherine Mansfield.

For almost eighty years, Mansfield has been popular with Chinese readers, influencing many Chinese short-story writers. It is unusual for a Western writer to have such an enduring impact, but little has been known of this phenommenon in the West - until, that is, the 2001 publication of A Fine Pen: The Chinese View of Katherine Mansfield.

Authored by Dr Shifen Gong, who has a Ph.D. in comparative literature from the University of Auckland, the work is composed of twenty critical texts selected and translated into English by Gong. As well as introducing fresh Asian voices to the largely Eurocentric criticism of Mansfield's work, Gong’s book provides a related commentary on Chinese literary history.

Many of the texts - which were written between 1923-1991 - are written by translators. The earliest piece is by a young student, Xu Zhimo, who reverently described his meeting with Mansfield in London as 'twenty immortal minutes.'

The story of the rises and falls in Mansfield's popularity is fascinating, as it moves in concert with the major social, political, and literary trends that have given rise to modern China and its literature. Two distinct periods emerge: the two decades before the Second World War and subsequent Japanese occupation, and the latter years of the 20th century, when the grip of the cultural revolution had relaxed.

Mansfield's portrayal of class and the injustices of bourgeois society were highly appreciable social themes for Chinese writers. One of the translators, Tang Baoxin, writes: 'With remorseless irony she lays bare the hypocrisy and shallowness of the leisured class and their men of letters.'

A Fine Pen also includes notes on the texts and a bibliography of Chinese translations and criticism of Mansfield's work from 1923-1991. The book supplies many insights into the reception of Western literature by Chinese readers as well as being a significant contribution to Mansfield studies in its own right.

Russian World of Katherine Mansfield (9/10/01)

Written by Joanna Woods, Katerina: The Russian World of Katherine Mansfield (2001) looks at the impact of Russian culture on the imagination and writing of Katherine Mansfield.

Though Mansfield never visited Russia, her life-long passion for the culture is evident in her letters and notebooks. Katya, Katoushka, Kissienka and Katerina were just some of the names she used at the height of her Russian phase, during which she also wore Russian dress, smoked Russian cigarettes, attended Russian concerts and embarked on a literary love affair with Chekov.

'Makes more sense of Mansfield's last months than anything I have read,' writes Mansfield scholar Vincent O'Sullivan.

New Mansfield Poems Discovered in U.S. Library (05/2015)

In May 2015, 26 previously unknown Mansfield poems were discovered in Chicago’s Newberry Library. An auction dealer’s sale entry found alongside the texts confirms that Mansfield attempted to sell the entire collection after her publishers refused to print her work.

Gerri Kimber, who uncovered the poems, traced them back to Mansfield’s ‘hedonistic’ period in the early decades of the 20th century, and remarked that the finding would yield ‘literary gold’ for Mansfield scholars.

The subjects handled within the verse are drawn from Mansfield’s own experiences, and depict – among other things – the memories of her childhood, and the emotion of her love affairs.

New Otago University Press Publication of Mansfield’s Urewera Notebook (05/2015)

The Urewera Notebook by Katherine Mansfield, a newly transcribed edition of the diary Mansfield wrote in 1907, was published by Otago University Press in May 2015.

Edited by Anna Plumridge, the publication includes critical essays and historical details that give context to the contents of the notebook, which Mansfield filled during a camping trip around the North Island as a 19-year-old.

As a written account of her last year in New Zealand, the Urewera Notebook is of immense value to the Mansfield researcher and enthusiast, illuminating the writer’s attitude toward her colonial homeland.

Last updated April 2016.

MEDIA LINKS AND CLIPS

- The Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- A Portrait of Katherine Mansfield: 1986 documentary that examines Mansfield's life and writing

- Biographical essay in Kotare 2007, Special Issue - Essays in New Zealand Literary Biography Series One: 'Women Prose Writers to World War I'

- There is a bibliography in the Auckland University Library's New Zealand Literature File.

- There is a page on Katherine Mansfield on the 'New Zealand Heroes' section of the NZEdge.com website

- The BNZ Katherine Mansfield Short Story Awards celebrate the work of New Zealand's fiction and non-fiction writers.

- The New Zealand Post Mansfield Prize sends a New Zealand writer to live and work in France each year.

- Julie Kennedy is the author of Katherine Mansfield in Picton.

- Katherine Mansfield Birthplace website